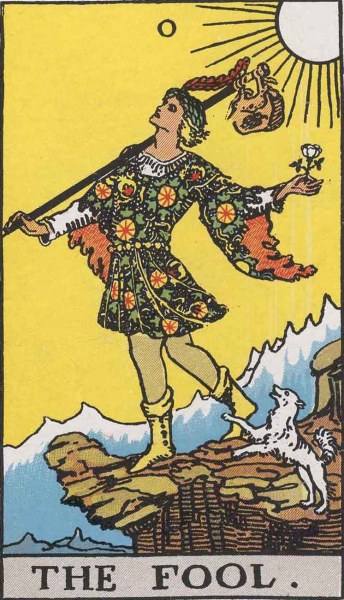

Take a look at most modern tarot decks, and you’ll notice that they all revolve around the same set of archetypal images. The 3 of Swords is a heart pierced by three blades. The Fool walks off a cliff with a white dog at their heels. The Magician stands behind a collection of magical tools, with one hand raised to the sky and the other pointing to the Earth. But who first designed these cards? How did they come up with images that were so compelling that artist after artist uses them for inspiration?

Although a man named Arthur Waite usually gets all the credit for creating the modern tarot, a forgotten hero named Pamela “Pixie” Colman Smith was actually the creative genius behind the cards. Smith was known as a spirited and irreverent artist, occultist, and performer in the 1800s, and now, thanks to the intersection of third wave feminism and occult practices like the tarot, her legacy is being rediscovered.

Who Was Pamela Colman Smith?

Smith was born in London in 1878 to American parents, and her childhood was full of travel. When she was ten, Smith and her family moved to Jamaica, where her father had taken a job with the West India Improvement Company, and Smith spent the rest of her childhood absorbing Jamaican culture and making frequent visits to relatives in Brooklyn Heights, New York.

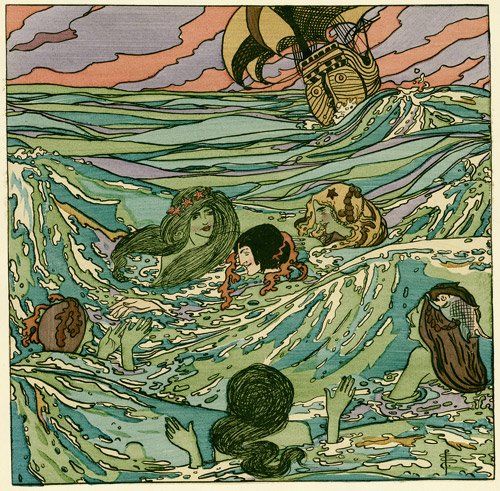

From an early age, Smith proved herself to be a talent artist, and after studying at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, she took various jobs in illustration and design. Smith also followed the New York theater scene from her home in Jamaica, and became known for the intricate miniature plays she wrote, designed, and performed herself. One of her plays, Henry Morgan, was a hit in Kingston, and Smith later performed it in New York, where it received even more acclaim.

Smith was also interested in Irish and Jamaican folklore, which heavily influenced her work. In 1899, she published Annancy Stories, a book of Jamaican folktales centering on the trickster god Anansi, and she would later go on to perform Jamaican folktales for English audiences. She also illustrated a volume of poems by W.B. Yeats, although it wasn’t published.

Smith’s friendship with Yeats would eventually lead her to the Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society dedicated to mysticism and the occult. It was there that she met occultist Arthur Waite, who wanted to publish a reimagined version of the tarot.

The Rider-Waite Tarot

The tarot began as a card game in the fifteenth century, with 22 illustrated trump cards and 56 pip cards, and there’s a long recorded history of people using tarot and other playing card decks for fortune-telling. One problem with older versions of the tarot, though, is that the pip cards aren’t fully illustrated. Instead, they contain very simple representations of their suit and number: for example, the 10 of cups simply depicts ten cups. Waite wanted to create a fully-illustrated deck, with scenes on all 78 cards, but he wasn’t an artist himself.

When Waite met Smith, he commissioned 78 illustrations for the new deck, but he didn’t have a high opinion of her. In his 1938 autobiography he dismisses Smith as a “draughtswoman” who “had drifted into the Golden Dawn and loved the Ceremonies … without pretending or indeed attempting to understand their subsurface consequence.” Waite considered Smith an artist who needed “proper guidance,” with some images needing “to be spoon-fed carefully.” It’s clear that Waite considered himself the mastermind behind the Rider-Waite.

There’s plenty of debate, though, over whether Waite’s attitude was justified. For instance, although it seems that Waite did dictate much of the imagery for the Major Arcana (the modern name for the 22 trump cards), he largely left the design of the Minor Arcana (the pip cards) to Smith. Although he gave her some keywords to work with, the iconic images of the Minor Arcana mainly came from Smith’s imagination.

The Rider-Waite tarot deck came out in 1909, cementing Smith’s legacy as an artist and mystic. However, Waite received the lion’s share of the credit, with the deck’s title combining the name of the publisher (William Rider & Son) with his own.

Pamela Colman Smith’s legacy

According to researcher Elizabeth Foley O’Connor, it’s impossible to know Smith’s race, but she was still plagued by racism throughout her career. Smith also had to deal with sexism in the illustration and publishing world. Problems with publishers led her to start a small press called the Green Sheaf Press, and after the Rider-Waite Tarot was published, she got involved in the women’s suffrage movement. Smith never married or had children, and there’s some speculation that she might have been a lesbian.

Recently, there’s been a revival of interest in Smith’s work among both artists and occultists, and newer editions of the Rider-Waite have changed the name of the deck to the Smith-Waite in order to credit her. In a 2018 roundtable for Bitch Magazine, actress and tarot reader Rachel True (The Craft) shared her insights on why Smith is such an important figure to women tarot readers:

I’m excited that there’s a global community out there, because when I started with tarot I didn’t know about Pamela. I knew the name on the deck, but I didn’t know the history behind the person. Knowing that we had a stake in [tarot] is affirming. I also think about her and how it might have been hard for her to only represent Anglo people in the cards. I wonder what her process was like; there must have been a sense of isolation, which I can relate [to] as an actress who came up in the ’90s and had to work in a predominately white industry. I feel like she must have been an artistic dreamer and there’s a little bit of isolation in that as well.

Unfortunately, the original drawings and printing plates for Smith’s tarot deck have been lost, so we’ll never know exactly how she envisioned the cards. Still, her work lives on in the hundreds of artists who have drawn inspiration from her work in their own decks, and the countless tarot readers who have found meaning in the symbols and archetypes she brought to life. Next time you sit down with the tarot, thank Pixie.

For more about Pamela Colman Smith, check out Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, edited by Stuart R. Kaplan.

(featured image: Wikimedia Commons)