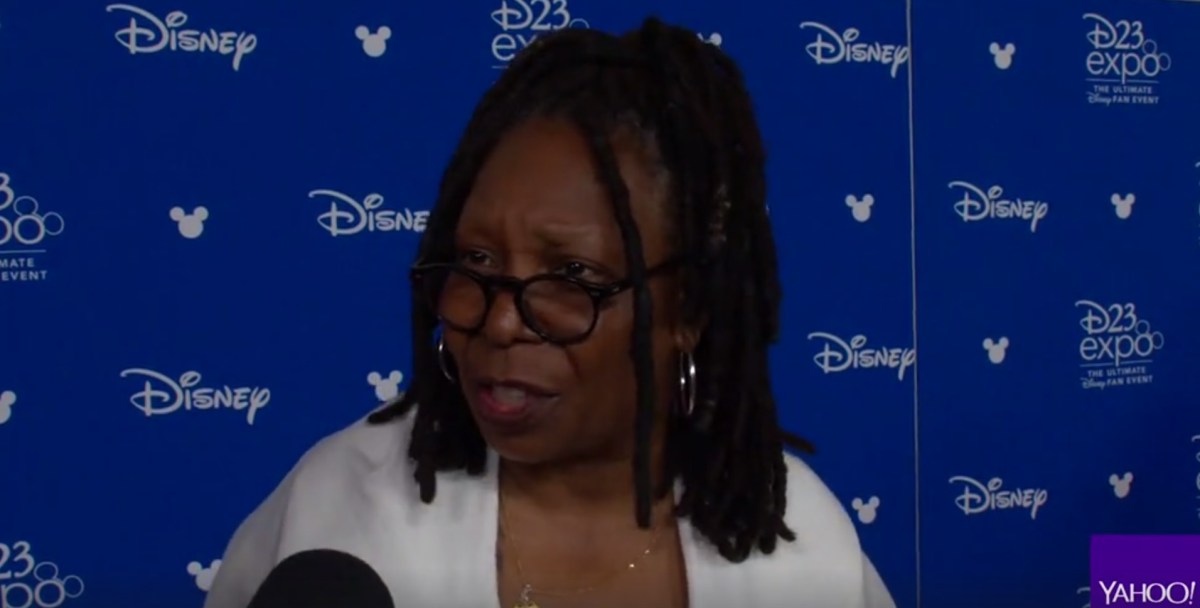

Whoopi Goldberg, along with other luminaries like Oprah Winfrey, Stan Lee, Mark Hamill, and Julie Taymor, was honored at D23 this year as a Disney Legend, the highest award Disney bestows on performers and creatives. As she talked about the honor and her favorite Disney films, she brought up one of Disney’s most controversial titles: Song of the South.

In the above video interview with Yahoo! Movies, she says, “I’m trying to find a way to get people to start having conversations about bringing Song of the South back, so we can talk about what it was and where it came from and why it came out.”

Since it’s been a minute since Song of the South was re-released in theaters, and many of you might not have ever seen it, because it’s never been released on home video in the United States, here’s a refresher:

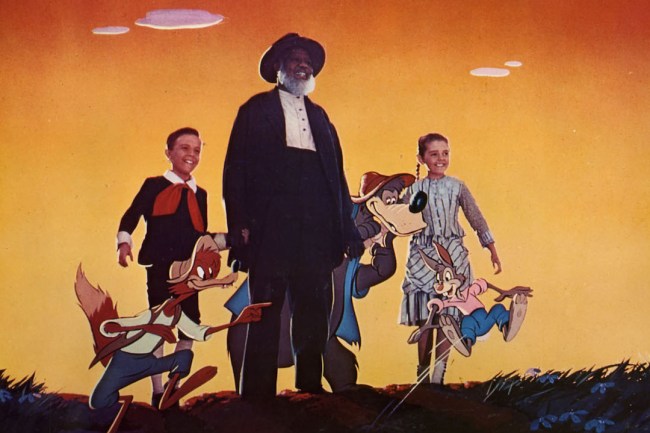

Song of the South is a 1946 Disney film that was a live action-animation hybrid. It’s based on the collection of Uncle Remus stories as adapted by Joel Chandler Harris. The film takes place in the U.S. South during Reconstruction, a period of American history after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. The story follows a little boy named Johnny who visits his grandmother’s plantation for an extended stay. Johnny becomes friends with Uncle Remus, one of the workers on the plantation, and takes joy in hearing his stories about Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox, and Br’er Bear. The stories help Johnny cope with life’s challenges.

Song of the South made history when Disney cast James Baskett in the role of Uncle Remus, making a black man the first-ever live-action actor to be cast by the company. It’s also an important film, in that it’s made people more aware of its source material. According to Snopes:

“Harris, who had grown up in Georgia during the Civil War, spent a lifetime compiling and publishing the tales told to him by former slaves. These stories — many of which Harris learned from an old Black man he called ‘Uncle George’ — were first published as columns in The Atlanta Constitution and were later syndicated nationwide and published in book form. Harris’s Uncle Remus was a fictitious old slave and philosopher who told entertaining fables about Br’er Rabbit and other woodland creatures in a Southern Black dialect.”

However, the controversy stems from how the stories were translated into a film, with many saying that the portrayals of black people in the film’s live-action framing device are racist and insulting. Song of the South glosses over the effects and history of slavery and despite taking place during Reconstruction, the black people in the film are still catering to the white plantation family.

Folklorist Patricia A. Turner brings up the one black child in the film, Toby, and talks about how his entire purpose seems to be to entertain Johnny all while the adults in the film cater to the white children at his expense. She writes, in part:

“Kind old Uncle Remus caters to the needs of the young white boy whose father has inexplicably left him and his mother at the plantation. An obviously ill-kept Black child of the same age named Toby is assigned to look after the white boy, Johnny. Although Toby makes one reference to his “ma,” his parents are nowhere to be seen. The African-American adults in the film pay attention to him only when he neglects his responsibilities as Johnny’s playmate-keeper. He is up before Johnny in the morning in order to bring his white charge water to wash with and keep him entertained.”

So yes, this film very definitely has problems, and is a product of a very racist time. So, does that mean Disney is doing the right thing by keeping it under wraps? Goldberg doesn’t think so.

In addition to Song of the South, Goldberg also brings up the 1941 Disney film, Dumbo, bringing attention to the crows (the Jim Crows?) that sing the classic song, “When I See An Elephant Fly.” She says, “I want people to start putting the crows in the merchandise, because those crows sing the song in Dumbo that everybody remembers. I want to highlight all the little stuff people sort of maybe miss in movies.”

According to Cartoon Brew, Goldberg posited a similar position when appearing at the beginning of Looney Tunes DVDs saying, “Some of the cartoons here reflect some of the prejudices that were commonplace in American society, especially when it came to the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. These jokes were wrong then and they are wrong today, but removing these inexcusable images and jokes would be the same as saying they never existed, so they are presented here to accurately reflect a part of our history that cannot and should not be ignored.”

Not releasing Song of the South seems silly in a world where people can freely watch D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. It also seems hypocritical of Disney to not release Song of the South due to concerns about racism when both the aforementioned Dumbo has been made available globally, and when Song of the South is currently available in countries outside the United States. So, the racism is okay, so long as Americans can’t repeatedly yell at you about it?

I agree with Goldberg in that some things are important to keep around precisely because they are offensive and racist. There are large swaths of our history that are uncomfortable to confront and look at, but that doesn’t mean we should’t. Contrary to what a lot of people believe, we are not living in a “post-racial” society. We don’t have the luxury of leap-frogging over discomfort to get to the part where racism has been eradicated.

Keeping Song of the South under wraps isn’t stopping racism in our country, but releasing it could help illuminate and explain it. For the same reasons that film schools keep teaching The Birth of a Nation, and you can still go into most bookstores and pick up a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, it’s important to have these relics of racism and bigotry around not only as a reminder of where we’ve come from, but to provide historical context for present-day struggles.

Having the film be available also keeps the positive aspects of the film from being erased, inspiring new generations to go back and read Harris’ original stories and learn more about where they came from, as well as remembering James Baskett’s contribution to Hollywood history.

Disney should certainly be kept in check with regard to present-day portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, but that doesn’t mean that we need to erase the mistakes of the past. The best use of mistakes is to review them so we can learn from them.

(image: screencap)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Jul 17, 2017 03:24 pm