Last year the TESA Collective, a gaming cooperative invested in creating tools and programs for social justice movements and organizations, Kickstarted a new board game called Rise Up: The Game of People & Power. I covered the Kickstarter over at Women Write About Comics and spoke with Brian Van Slyke, the game’s lead designer. As an aspiring teen librarian, I was interested in Rise Up’s potential as a tool for talking to kids about activism, and concrete actions we can take to participate in movements. Now that the game has been printed and is ready to play, Van Slyke gave me the opportunity to test it out with a group of kids at the library!

As many of you may know, summer is a busy time for public librarians. School’s out, summer reading is in full swing, and in addition to open programming, we also host outreach groups from various organizations. I played the game with a group of campers, ages 11-13, who are visiting the library regularly this summer. What follows are the details of how I planned and ran a Rise Up program designed to give kids an idea of what a movement is, actions activists take beyond protest marches and sit-ins, and to be a fun activity!

Set up

Because I was working with an outreach group I’d already met, I knew I’d have about 20 kids in attendance, plus some volunteers who I believe were 13 and 14 year olds. I set up the games beforehand, with all the movement, system and supporter pieces in place. Additionally, since this was a younger group and a large one, I used the simplified version of the game, which doesn’t include the skill cards.

We also started off with the character pieces placed on the board, but because the players have to pick which piece they want, I’d recommend leaving them in the box or sitting on the table, so the players can look through them and place them themselves.

On Van Slyke’s suggestion, we planned to have four players per game board, but I also placed a volunteer at each table to help facilitate the game. This turned out to be a great choice—but I’ll get to that when I discuss gameplay.

Designing the Movement

The first step of learning how to play Rise Up is gaining a basic understanding of what it means to build or be part of a movement. I wanted to give our participants an example that demonstrated how young people can be activists, and I was fortunate to come across this Teen Vogue article about a protest at the Texas State Capitol that happened the day before my program. Texas’ state legislature just passed SB4, a bill that bans sanctuary cities and allows police officers to ask detainees about their immigration status. Teen girls donned quinceañara dresses, danced on the capitol steps, and then headed into the building to try and meet representatives. I was very taken by the image in the Teen Vogue article of the girls in their dresses standing with fists raised, and I started with this as my example: movements are what we create when a system (like a government) does something wrong that hurts people. We use various tools, often tools unique to who we are, to stand up and say no.

After giving a real life example I also gave a fantasy example. The how-to-play instructions in the game offer an example using dragons, but I used a bizarre scenario about cat people oppressing dog people. Then, we created our story for the game together. To save time, you can come up with a story beforehand that you think will appeal to the players, but ideally building the story as a group will create more buy-in. I asked the kids to give me a few ideas, and then we’d vote on which we wanted to play. We ended up with “fire breathing cats poisoning everyone,” which was the most exciting suggestion.

I want to pause here a moment and talk about something unexpected that happened during the story development. A kid mentioned Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights movement as a possibility, and a young black girl immediately got upset and told him that was a real thing that happened, not something funny. I responded that yes, that was a real thing that was and is still happening, and this game isn’t just meant to be funny; it’s also about real life, and real movements. When we voted, I omitted this suggestion from the vote.

This was a moment that I hope I handled well, but am open to discussing further. I’d met each of these kids only once prior to running this program, and I’ll only see them twice more for what will undoubtedly be chaotic programs before possibly never seeing them again. In a space where I have little built-up rapport with the kids, and I’m constantly being pulled in ten directions, it’s difficult to talk in-depth about anything. Additionally, I work in a diverse neighborhood with a large population of immigrants, and our participants were largely kids of color whose lives are deeply affected by American politics. Rise Up is a fun game and an opportunity for creative storytelling, but it’s also an opportunity for open discussion about the injustices that affect our lives. Because of our time constraints, I didn’t aim to have lengthy, deep discussions, but to plant seeds that would help the kids feel like they have some power in a tumultuous society that is often against them. It’s important that the library provides opportunities for them to play, be carefree and be happy, but we are always whole people, and we never leave our identities at home.

Teaching participants how to play

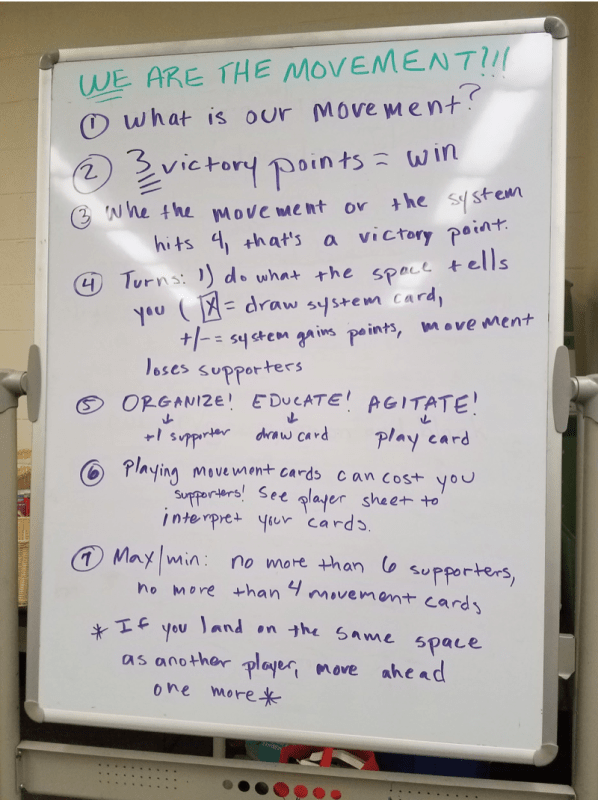

Each Rise Up board comes with a booklet of instructions that outline simplified and standard play. Additionally, TESA created a video that walks through the instructions for playing the simplified game. I decided not to use the video, but to make things easier on myself, I pulled out key points I wanted to cover and wrote them on a whiteboard. Players could of course reference these during the game, but I don’t think anyone did. However, I was really grateful to have them there!

(image: Alenka Figa)

(I’m not a great artist, otherwise I would have drawn the symbols from the game.)

For the story building portion, everyone sat on the carpet at the front of the room, but before explaining gameplay I had them sit at the tables so they could look at the player cards and pieces. I also instructed them to not touch anything, so of course they did! However, the boards stayed pretty much intact.

Once everyone was seated and quieted down, I went through each point from the whiteboard in order: the goal of earning three victory points for the movement, what constitutes a turn, how movement cards work, and the maximums and minimums. A common problem of mine is talking too fast, so while you may not have this problem, I’ll caution you to take your time and point to the game boards as much as possible. Once I’d explained everything I took a couple questions, but quickly picked a person at each table to go first, and had them start playing.

Gameplay

Here I’ll give you my first regret: not having each table go through their first turn together. If I run this again, I’ll have a player at each table roll the die, count spaces, tell the room where they landed, and organize, educate or agitate. Instead, I went from table to table and eventually ended up doing just that: running through a full turn or two with the kids until they fully understood gameplay. I suspect that, should you play adults instead, running through that first turn together will still be beneficial.

This point of the program is where the volunteers became essential. Once the volunteers—who, by the way, were now “the system” and read system cards for us—understood the game, their tables became essentially independent!

Younger players tend to focus just on gameplay and forget the story, so when I helped out at a table I’d have them read the actions on a movement card which I would then spin into the fire-breathing cat story. “We take time to help out our neighbors and build our community,” becomes, “We help our neighbors rebuild a home destroyed by cat fire!” One table did get very into the story and a player did something I found fascinating: he sabotaged his teammates, choosing to hang on to useful movement cards and eventually letting his supporters go down to zero, causing their movement to fail. I think the cats set everything on fire in that game!

Wrap up

I left a little time at the end for Roses and Thorns, an activity that you may be familiar with if you’ve worked with kids. Each participant has to think of a rose—one good thing that happened, or something they enjoyed—and a thorn, something that they didn’t like.

Common roses were statements like, “We got up to two victory points!” or “The movement got a victory point,” or, “I got six supporters!” Thorns were mostly kids who were confused because I went too fast or, for one unfortunate group, who weren’t grasping the game and eventually gave up on playing. Coincidentally, guess which group had the only volunteer who didn’t try to help their kids play? Yup, that group! However, the majority of kids said they had fun, which was a main goal achieved!

My favorite post-game discussion was with the group containing the player that self-sabotaged. I saw that player again a week later, said hello and asked him if he had any regrets. The answer? Nope! He was absolutely tickled by the idea that he’d had the power to make his team win or lose. He’d been playing with friends. I let the kids chose where they sat and who they played with, so his fellow movement members still had fun, but they were a little bothered by having lost. I explained that this a real problem that crops up in movements; participants find they have opposing goals or ideals, things go sour, and the movement falls apart.

With programming for kids this age (and even older), I like to embrace the chaos and see what comes out of it. I found it valuable to discuss the quirkier occurrences like sabotaging your team, but also enjoyed celebrating successes, even small ones, like earning the highest number of supporters possible. (This isn’t necessarily a goal in the game, but the kids were very fixated on it!) Rise Up is beautifully designed. Each success and failure communicates to incidents that happen in real life movements.

Now that I’ve had time to reflect, the number one thing I’d change would be leaving more time for the group to process post-game. We had such interesting experiences while playing, and I wish I’d had more time to tie them back to the story and relate them to real movements. If I were to run this program again—and I hope to—I would cap the number of participants based on how many staff are available to run the games. (I cannot stress enough how essential it was to have those tween volunteers at each table!)

Extending the length of the program would also allow us to spend more time building the story both before and throughout the game.

If you’d like to buy Rise Up for your library or for yourself, it’s now available on TESA’s online store! I’m also happy to answer questions about the program in the comments. Ask away!

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Aug 4, 2017 02:25 pm