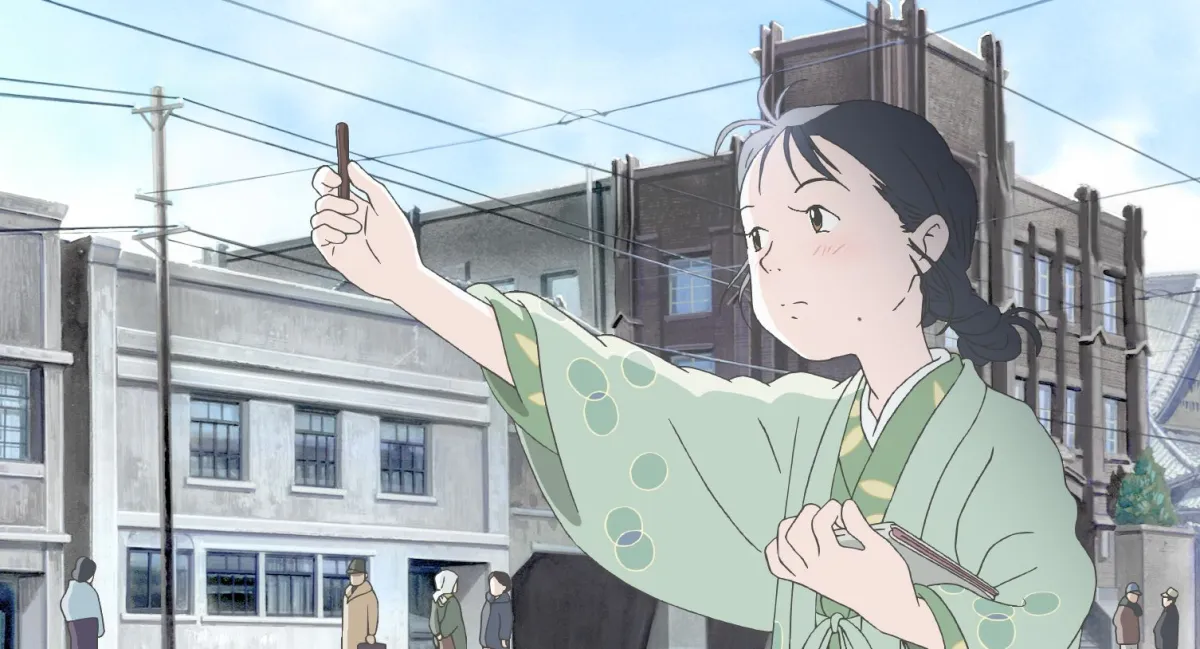

Sunao Katabuchi’s In This Corner of the World, an animated film about a young girl and her family during World War II, has been gaining attention for its realistic portrayal of the time period. Recipient of the Animation of the Year award from the Japan Film Academy and the Peace Film Award from the Hiroshima International Film Festival, Katabuchi’s film zooms into the everyday life of Suzu, as she moves to Kure after getting married.

This isn’t a film about the battlefield or from the airplanes, but instead one about how life changes when battleships begin gathering in your seaside town, air raids start becoming regular occurrences, and you’re forced to make do with limited resources. Based on Fumiyo Kōno’s (sometimes romanized as Fumiyo Kouno) manga, Katabuchi calls his film “almost a time machine” for a history he’s passionate about preserving.

In a conversation with help from translator Junko Goda, we talked about the urgency of the story, as well as the intensive research the team did to represent this history. When I asked the director what moved him to make this film, he cites a Q&A in Anaheim from 2011, where he announced his next film would be “set in Hiroshima 1945.”

In terms of timing, Katabuchi calls it a timeless story, but adds that “there’s not that many people left to remember World War II.” The director, who heard many of these stories from the generation before him, wanted to use that familiar storytelling, but also to go beyond them with extensive research.

“My parents and also Ms. Kōno’s, our parents are the ones who remember the war. But, granted yes, our parent remember the war but they were still children. All of the folk who were adults during the war now are in their 90s. We grew up hearing stories from our parents about the war, but it was really from the point of view of children so now, at this point in my life, I felt that was important to look at the war from the point of view of an adult. I realized there’s a possibility—and I can say this for myself, maybe for Ms. Kōno as well, but there’s a possibility that all these experience will disappear with them.

I didn’t want to be stuck in having this point of view of the war from when our parents were children, I didn’t want to just be stuck with the point of view of a child about that time. So as those who experience the war—as we lose more of them—I felt we really needed to capture all those stories for now.”

Katabuchi tells me about the reception of the film, and how they invited “folks in their 70s, 80s, and even their 90s” to watch the film. “Their comment was that when they watched the movie, they really felt like they were there,” he says, “the sights and smells really came back to them.”

“So, we were really encouraged after the movie came out, that timing-wise it was a good time to be able to recapture what that time was like and then those folk in their 70s, 80s, 90s, being able to tell us, ‘Yes, that is what I remember from my childhood.’ They were able to say, ‘Yes that’s what it was like during the air raids. I remember it sounding like that.'”

In many ways, the director points out, these screenings spoke to a certain timeliness. “If we set out on this production ten years from now, we might now have been able to experience that,” Katabuchi suggests.

One of the most compelling parts of In This Corner of the World is its commitment to Suzu’s story. When I share with Katabuchi that I feel like a lot of war stories are told from the battlefield, or from the skies of these air raids instead of from the ground, he shows me a black and white photo of Kure through screen-share.

“I think because we don’t live in the battlefield, we don’t live in the airplanes—we live on the earth. A lot of heroes, they fly…I feel that we are a species that lives on the earth and we look at the sky with yearning. I think that’s why there’s a little bit of—there’s a specific word in Japanese but the human species is very resilient but there’s still something in the sky. We look forward and we want it, we want to be up there too. There’s a tinge of sadness.

This is a picture of Kure, 1945. March 19th. And Suzu’s probably around here. You see this photo, but you can actually pinpoint the one person that lives in this city. And just to really realize that—yes, this is a photo but there are people living here. For the point of view of this overhead shot, you don’t see any of that. But in this photo there’s tens of thousands of people living here.

And this could be any one of us, we could be one of these ten thousands of people living here. I think that’s really important.”

That sense of loss and connection is shown not only in violence, but in small ways as well. If you watch the trailer, Suzu is portrayed as an artist and the film is punctuated with moments of her drawing in a sketch pad. One early childhood memory emphasizes her childhood talent for painting, and how it fosters a connection with another young boy. “I think that had there not been a war there would’ve been a different story about becoming an artist or doing more drawings and pursing that,” says Katabuchi, “But the reality is that during wartime, it’s a useless skill. So for Suzu, drawing is very important but in the context of war, it’s a useless skill. So I really wanted to represent that kind of sadness, that missed opportunity because of circumstances.”

Historical fiction is a difficult genre, and portrayals of war can also be incredibly challenging in terms of romanticization, accuracy, and sensitivity. I enjoyed In This Corner of the World, but after hearing more about Katabuchi’s dedication to detail in the film, I appreciated it even more in terms of the attention paid to these fiction characters. “Everything you see, as far as the landscape, the buildings, those are all correct as it was during the time,” he says. The director points me to a spreadsheet, and explains, “we researched what the weather was like everyday. We took all this real data and we dropped in Suzu and her family and people around her. We plot them in a very real world.”

“So we did research from the temperature, the tides, and what ships were docked at the port every day. We set everything up with the reality of the day-to-day in hopes that Suzu became a real person too, that could have been living in Kure. Suzu—she’s representative of all the people living there at the time. I think she really represents a real person at that time. So by putting her in a realistic world, I really hope that she became part of reality as well.”

Blue boxes indicate sunny days, greys are for overcast and cloudy, and purple are days that rained. When we talked about adaptation and tone shifts, the director notes that one scene in the original manga is changed, because it was lightly raining on that day. When weather is so often a plot device or a way to set tone, Katabuchi’s attention to this is impressive, especially when we talk about the history-changing event that comes the mind the moment you hear about the film’s setting and premise:

“Of course, I could have portrayed it very tragically when the atomic bomb is dropped, but realistically it was blue skies that day. It was a gorgeous day.

So, because we did our research it was a really cloudless sky.”

Director Katabuchi also shared with me sketches and images of clothing in the movie. He notes that the designs were taken directly from Kōno’s manga, and how “clothing actually is not something you wear once or a few times, it actually has a life after one person finishes wearing it. It gets sent to the next person.” Each outfit has a story behind it, he says, calling to mind the ways animated character often wear only one outfit or endless types of clothing. “It’s important to also look at how people live with limited resources. So we counted how much clothing each person has….that’s how we built the wardrobe, it’s an important part of life.”

In one instance, we look at the design and sketch for a kimono given to Suzu by her grandmother when she gets married. “But even a really nice kimono loses its value as a kimono in the context of war, in this box right here, the nice kimono gets traded in for pillows and fish and food.” In another image, he points out how one childhood yukata gets recycled twice to save material and goes through the specific memories behind it.

Although we watch the film knowing what will end up happening to Hiroshima and the Japanese, the focus is on the endurance and resilience of people in Kure. “I want to show that even with this extra layer of wartime that a year in the life of anyone would have ups and downs as well,” Katabuchi explains.

When I ask whether non-Japanese viewers might have a different viewing experience, he says he doesn’t anticipate a huge culture gap:

“Even for Japanese people this is an era where people don’t remember anymore. It’s starting to become this unknown point in time. And also culturally too, it’s a struggle to figure out what kind of culture it was at the time. On top of that, it’s a very specific place too. So also, in the movie itself, Suzu and her family they all speak in the Hiroshima dialect which isn’t widely understood in the nation. Not everyone would understand it.

So I don’t think coming into the movie—whether you are Japanese or not—you’re all coming into it with very little information about that time. So kind of on the same level.”

As for what Katabuchi hopes for viewers of In This Corner of the World, he says, “I’m hoping they discover a new world. To enter into this unknown world with Suzu as your guide. I think Suzu is a really good guide, and you lend your trust to her and trust that she’ll take you to the other side of the journey.

That’s what I hope for anyone who’s coming to see this movie.”

The film comes to the U.S. August 11, 2017 with both English subtitles and a dubbed version.

(image: Shout! Factory)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Jul 6, 2017 03:42 pm