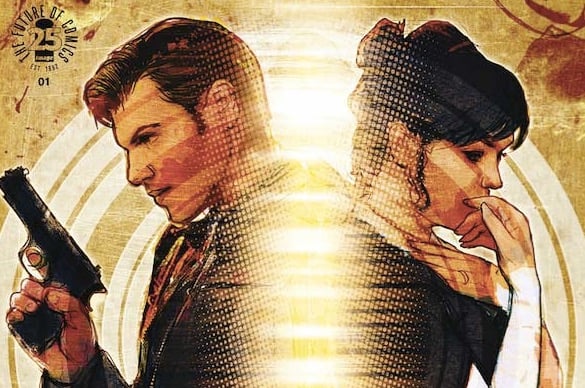

A frequent criticism of literary or visual media is the use of what have colloquially come to be known as “tropes.” (Yes, I see you, fellow pedants. A trope is actually meant to refer to figurative language, but its meaning has expanded in popular usage, and that’s totally fine.) Certainly, using stock characters and clichéd plot devices can dilute the impact of a story. But these conventions can also play an important role in furthering a narrative, particularly one that’s about subverting expectations. (You can’t subvert expectations until the reader actually has expectations.) Take, for example, Gail Simone and Cat Stagg’s new Image book, Crosswind, in which a hitman and a housewife swap bodies.

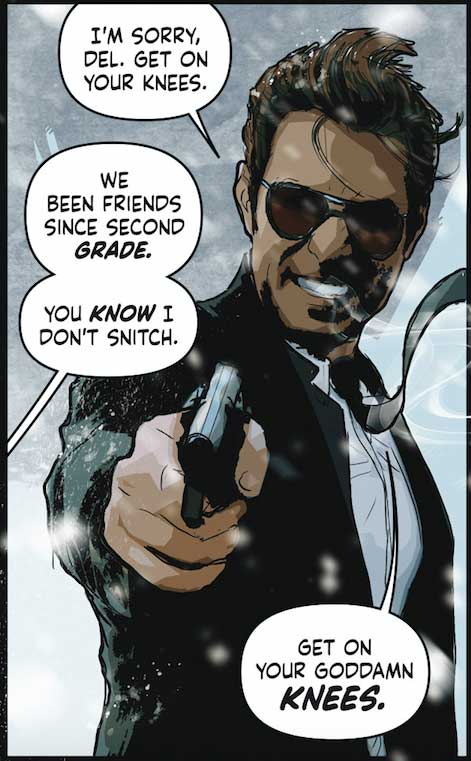

Picture an archetypical gangster hitman. He’s wearing a suit. He’s got a gun. Maybe he’s wearing sunglasses. He probably takes snitches out into the woods to execute them, in a flurry of swearing and stone-cold violence. There will almost certainly be a scene with a nearly naked lady. And of course, at some point in his gangster arc, things will tilt south. In a few deft strokes, readers understand the basic outline of Cason Bennett. We have a fair idea of how he’ll react in the types of scenarios his character can be expected to face.

Juniper Blue—a housewife who is bullied by her husband, her children, her neighbors—is in every way the opposite of Cason. Readers quickly understand how her worn-down, fragile self-confidence prevents her from standing up for herself as she is objectified and infantilized at every turn. Where Cason is capable, Juniper is unsure. Where he is aggressive, she is meek.

When a mysterious man casts some sort of spell over Cason and he swaps bodies with Juniper, the intersection of their lives shifts the plot from conventional establishing shots into real action. How is Cason going to react from behind Juniper’s eyes when her horrible husband treats her cruelly at the special dinner he’s ordered her to prepare for his boss? What is Juniper going to do when faced with the brutality that comes with Cason’s line of work?

It’s in these stark contrasts that clichés become absorbed into storytelling and transformed into something useful. They’re a way for readers to understand certain parameters of character and situation, acting not as a destination but as signposts guiding us toward the subversion of expectations that really make up the story. Building real stories and characters out of clichés is a particular strength of writer Gail Simone. Her legendary Red Sonja run, one of my favorites, turned the pulpy fantasy pin-up into an iconic feminist anti-heroine.

In comics, of course, writing is only half the story. Visuals like body language and facial expressions are essential to establishing the characters in Crosswind, before their lives are turned upside down. Co-creator and illustrator Cat Staggs sets out a recognizable physicality for Cason and Juniper, giving the swap a strong visual component rather than leaving it to play out in the dialogue. In suddenly off-kilter panels, Juniper’s face stretches into Cason’s sneer, while Cason recoils with Juniper’s horror at the scene of a grisly crime. This is a very smart touch that is sure to be important later, as Cason and Juniper attempt to navigate one another’s conflicts.

This book is surely about the folly of judging by appearances, so I hesitate to classify Crosswind as any one thing. It promises to be action-packed, humorous, gritty, and heartfelt. What could we learn about ourselves if we suddenly became our own opposite? I suspect the answer is that we’re all more alike than we know, and that none of us are stock characters at all.

Tia Vasiliou is a digital editor at comiXology and co-host of The ComiXologist Live, every Wednesday on the comiXology Facebook page at 4 pm ET. You can find her on Twitter at PortraitofMmeX.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Jun 23, 2017 11:51 am