What does every Spider-man film, Men in Black sequel, and my beloved Stuart Little have in common with one another? They were all produced and/or distributed by Columbia Pictures, now under Sony Pictures. Founded as CBC (each letter recognizing a founder of the company) in 1918, the founders quickly changed names in 1924 to establish themselves as the American movie company. The new name used the recognizable face and name of Columbia.

While the Columbia Pictures version is missing her sword (which there isn’t much evidence she used), American flag shield (think original Captain America), and looks pretty modern, the woman Columbia is a personified image of America. She represents things like republicanism, liberty, and forward progression. With a few key distinctions, she was the “It girl” before Lady Liberty, and it’s no coincidence that their stances are so similar. Like much of American iconography, Columbia both acts as something to work towards and was constructed as a means of propaganda.

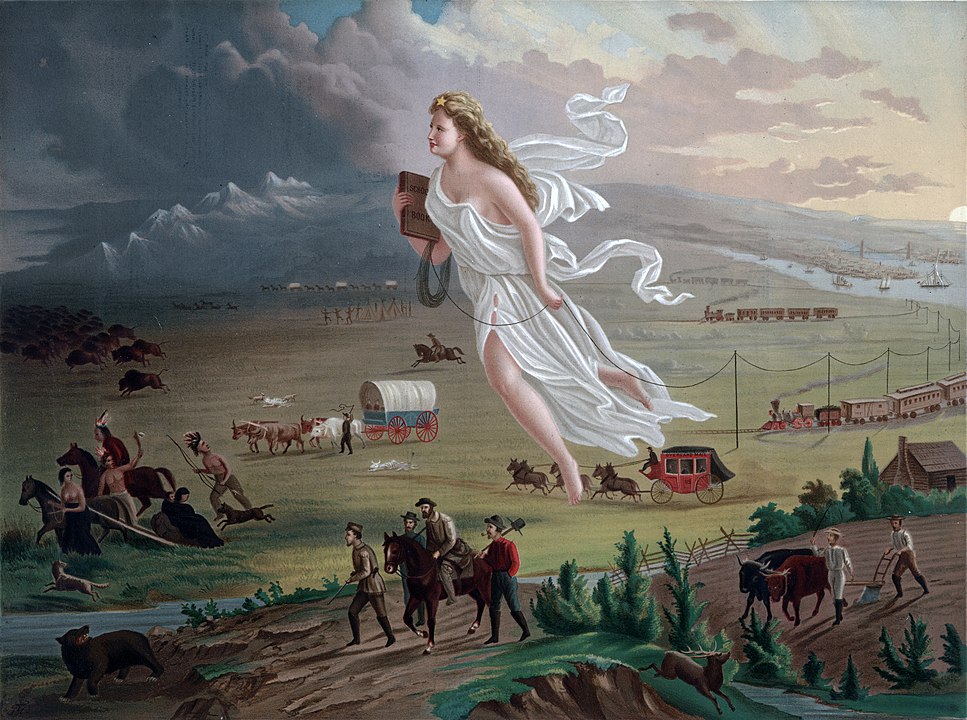

(Image: New-York Historical Society Library and Library of Congress)

When Columbia Pictures decided to take on this logo and name change, they inherited the good and the bad of the legacy. This is the same for other uses of the name, from the District of Columbia to Columbia University (one of America’s oldest universities), and carries a history as troubling as, well, that of this country.

Before Columbia

Like any “western” nation trying to justify its superiority and long-standing traditions, America, Britain, and others have pointed to the Romans (who pointed to the Greeks) and said, “I’ll have what they’re having.” Hey, there were a lot of exciting and cool things from those civilizations, but also, there is a reason why powerful institutions, from the government to museums and banks, replicate their ideas and aesthetics.

Romans designated a (plagiarized) goddess to many areas, and that goddess would serve as a personification of those people—like a mascot when literacy wasn’t typical. Britain had Britannia, and when the U.S. was still 13 colonies under British rule, our toga-wearing goddess was Amérique.

While portrayed as more European, Amérique had features in her presentation that combined the three races that made up the U.S. at the time—white, Indigenous, and Black. She fell out of fashion during the Revolutionary War for various reasons.

In response to rebellious behavior by colonists on the eve of the war, British papers drew Amérique as “savage” and showed loyalists defiling her. A gross personification of Britannia and her people assaulting Amérique’s chastity shows that violence against women weaponized as propaganda isn’t new. Like any child looking to rebel, America needed a new look, and one name was already kind of floating around: Columbia.

It was (mis)understood that Christopher Columbus was the first European to “find” America. Despite never traveling to any place that would even become the U.S., “ia” was slapped onto his name to make it sound more Latin. Even if made up, more Latin = more official = tradition. “Columbia” was used for America sometimes, but until there was a need to ditch Amérique and enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley penned it in her 1776 poem His Excellency General Washington, it wasn’t Facebook official, so to speak.

Manifest Destiny

While some uses of Columbia advocated for those in poverty (or other good causes), a bulk of what makes me cringe seeing Columbia still in use today came after the Revolutionary War—a.k.a when Americans turned their attention back to Native American genocide and displacement under the guise of “Manifest Destiny.”

As a reminder, Manifest Destiny was the cultural belief that American settlers were destined to expand across North America (coast to coast, or sea to shining sea). As a secular nation (on paper), a God-like figure couldn’t do this, but a personified Goddess (Columbia) could and employed widely understood Abrahamic references.

These are the declarations of a “promised land” and a “city on a hill” to serve as a beacon of light. Columbia is a white savior and a gentler hand upholding white supremacy. In the famous painting American Progress, she is bringing light and modernity to the dark west.

Light to darkness is another holdover thematic element used in the Enlightenment time when Europe began to idolize Ancient Rome. Light in the darkness is also what happens when you’re watching a movie in a theater.

(Image: Library of Congress)

In Roxanne-Dunbar’s book An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, she (like other historians) found that while the softened language of the harmful ideology seemed a relic of the past, much of it is still employed today. For example, Christian leaders/settlers from the 1700-the 1800s and contemporary right-wing Zionists refer to their violent displacements of Native people as ordained by God, and themselves as God’s chosen people fulfilling a preordained destiny.

This reflects settler colonialism’s persistence even beyond this continent, and Columbia was the figure leading the charge in America’s mission of Manifest Destiny. (See entire world-building of the 2013 game Bioshock Infinite.)

Her image was also a unifying one, claimed by all. During the Civil War, both the United States and the Confederacy used Columbia’s image and cried her name in battle. “Hail, Columbia” was the National Anthem before the “Star-Spangled Banner.”

After the war, Manifest Destiny served as a shared mission that helped reunify the nation. Federal troops, state militias, and everyday people united against a common enemy (Indigenous people.)

Even as Uncle Sam slowly became a part of the American pantheon of mythical figures, Columbia continued to serve her purpose. Uncle Sam represented the American government (and still does), whereas Columbia was a softer, feminine image of the American people. Values projected on her by American culture more often than not aligned with the American government.

Lady Liberty takes over, but Columbia endures in art

As U.S. imperialism expanded beyond the continental Americas and island nations (mostly possible because Europeans had to rebuild after WW1), we needed a new image. It was a new century, and Columbia looked like a relic of the past. Uncle Sam stuck around because we apparently needed a tough, patriotic figure to personify our response to the power vacuum of the post-WW2 decline of European Imperialism.

Columbia fell out of favor, and Lady Liberty became the new symbol of America. It took a while for The Statue of Liberty to catch on. Some reasons include the fact that France’s gift of the now-iconic statue was initially meant to celebrate the 13th Amendment, the average American’s attitudes about the French were never great, and Columbia was used to sell bonds and preach patriotism.

Lady Liberty’s staying power as a personification of America (and especially as a mother) wouldn’t come until the themes of the poem The New Colossus (by Jewish activist and writer Emma Lazarus) were adopted by immigrants and advocates as a symbol of hope.

I’m not Native American, so I don’t really know or have the right to proclaim where we should go from here or what we should do with this. However, at the bare minimum, we should reflect on how this anti-Indigenous imagery exists even outside of commercial items and school/professional mascots and do better. Columbia is not an Indigenous woman, but her existence and persistence directly connect to attitudes about Native Americans and America’s messy identity.

When discussing Native Americans and Hollywood, the conversation usually involves representation (casting and stereotypes) and activism. Still, at the start of a lot of films, as the most recognized woman in film, the image of Manifest Destiny endures through Columbia Pictures.

(Image: Columbia Pictures, Sony)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Nov 26, 2021 04:00 pm