Note: This post contains spoilers for Inside Man and references to sexual assault, including against children.

When I heard about Steven Moffat‘s four-part crime thriller on Netflix, Inside Man, I was cautiously excited. David Tennant as a vicar and Stanley Tucci as a crime-solving death row inmate? Yes, please! Even knowing Moffat’s history of sexism, I hoped that the talent of the cast would carry the show.

And … nope. I was disappointed. Tennant, Tucci, and the other cast members are great, but the plot is so absurd that the whole series becomes a lesson in how not to write a story.

The plot focuses on Harry Watling (Tennant), a vicar who’s confronted with an uncomfortable request. Edgar (Mark Quartley) a parishioner who’s living in an abusive home, wants Harry to hide a flash drive full of porn from Edgar’s violent mother. It’s a weird request, but not out of the realm of possibility, especially if you read it as a cry for help. From there, though, things take a wild turn.

Instead of leaving the flash drive in his church office, which Edgar says is the last place his mother would look for it, Harry inexplicably takes it home with him. Astonishingly, he casually tosses it in a dish by the front door along with his keys, and his son Ben (Louis Oliver) gives it to his tutor, Janice (Dolly Wells), when she needs to save some files. Somehow, the photos on the drive instantly appear on Janice’s screen, and she sees that the drive actually contains child pornography.

As if that chain of events isn’t implausible enough, Ben tries to cover for his father by claiming that the porn is his, not knowing what’s actually on the drive. Harry lets his son take the fall, but then panics when Janice tells him about the child pornography. Janice is convinced that Ben is a pedophile, so Harry locks her in the cellar to keep her from telling the police. He then tries to wring a confession out of Edgar, eventually driving him to suicide.

Why Inside Man doesn’t work

The premise of the series is that anyone can be a murderer under the right circumstances, and the narrative desperately wants us to believe that Harry is an ordinary guy who’s suddenly thrust into an extraordinary situation. The problem is that the series can’t decide if that’s actually true or not. Is Harry a good enough person that we should care what happens to him, or a bad enough person that he would handcuff a woman to a pipe in his cellar? The series fails at convincing us that he could be both.

What makes the plot even more troubling is that all the characters ignore the biggest, most harmful and time-sensitive problem staring them in the face: somewhere, the children in the photos are being sexually abused, and they need help. While Harry and Edgar try to cover their own asses and Janice schemes in the cellar, children are suffering irreparable harm. Any character who doesn’t see that situation as a priority isn’t worth the audience’s sympathy.

But that lack of empathy is fitting, honestly, in a show so committed to gratuitous sadism. The series begins with an extended scene on a train in which a guy sticks his crotch into journalist Beth Davenport’s (Lydia West) face, while she sits silently, paralyzed with fear. Another woman takes a photo, and the guy demands that she give him her phone. She does it, hanging her head. What? I’m sorry, does Moffat think that complete, unquestioning submission is the only response women are capable of?

The main problem with Inside Man is that every character seems to operate according to what would theoretically make a good thriller plot, instead of what actual human beings would do—I mean every character. Beth is simultaneously comfortable interviewing murderers on death row, and too terrified of men to stand up to a pervert on the train. Tucci’s Jefferson Grieff, who solves crimes from his prison cell, is presented as a Sherlock Holmes-style genius, but he seems more like a clairvoyant. Why? Because he deduces things that no real person could ever guess at, because there’s no way those things would ever actually happen. Nothing in this series is at all plausible.

If there are any budding writers reading this, take note: If you want to write good characters, they have to act like real people. You can have the most farfetched plot in the entire world, and it’ll work if your characters respond in ways that are believable. But if your characters’ choices make no sense, then even the most clever premise will fall flat on its face.

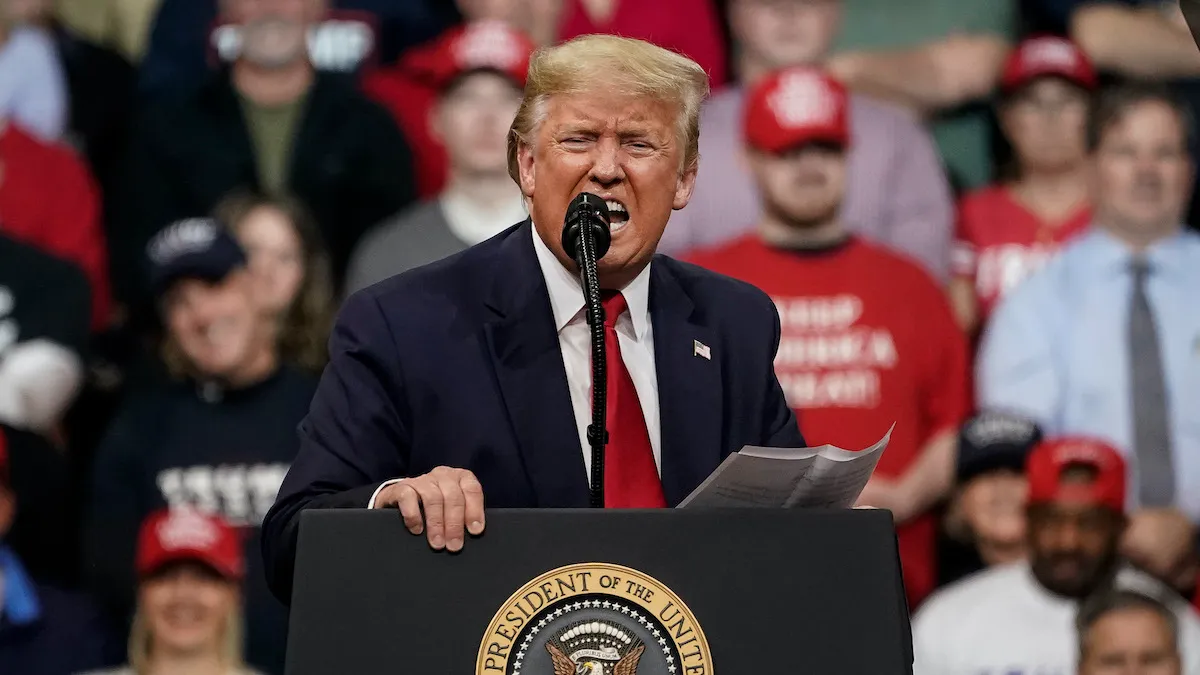

(featured image: Netflix)