In one scene of Hari Kondabolu’s truTV documentary The Problem With Apu, actor and former White House worker Kal Penn pauses before answering whether or not he’s regretted an acting role, and says he’s realizing that he’s not in a PR event. “I was wondering if anybody would love that as much as I did,” says Kondabolu when I bring it up, “That was for me and anybody who understood that it’s always the same thing.”

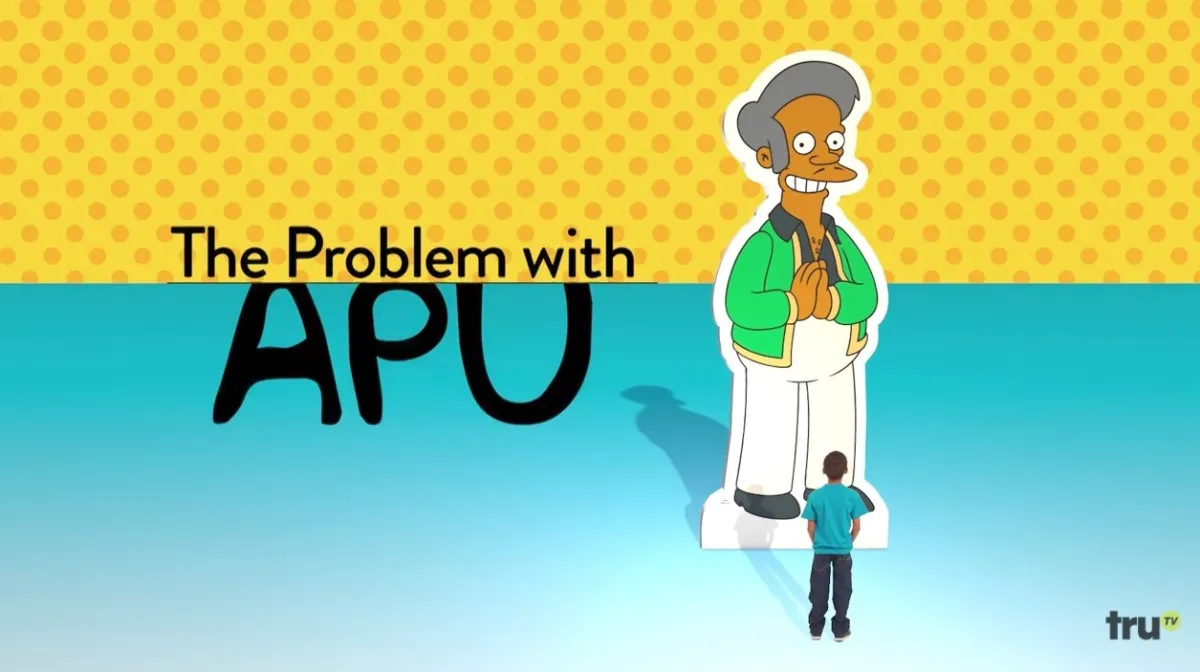

In one part, The Problem With Apu is a film about Kondabolu’s dislike for The Simpsons‘ Indian character Apu Nahasapeemapetilon and efforts to see if voice actor Hank Azaria will perhaps stop doing that terrible voice. While the comedian admits that he loves the show and even cites it as a huge influence, the words “Thank you, come again!” have followed the comedian for 28 years. Though Kondabolu may call The Simpsons “one of the main reasons I knew you could be smart and funny and political at the same time”, his documentary shows you can unfortunately be smart and funny and political and racist at the same time. However, The Problem With Apu is also a larger, more ambitious project that brings together South Asian talent to talk about the importance of representation in a series of candid and personal interviews.

@KalPenn and @HariKondabolu aren’t the only ones who have a problem with Apu. #TheProblemWithApu premieres Sunday at 10/9c on truTV. pic.twitter.com/FwLbXXRDLN

— truTV (@truTV) November 14, 2017

In a phone interview, I talk to Kondabolu about making the documentary and how he navigates being a comedian that takes on lots of issues about race. Some quotes have been edited for clarity.

So why Apu? And why now, after he’s been a part of the show since 1990? Well, Kondabolu traces the beginnings of the documentary to a 2012 segment on Totally Biased With W. Kamau Bell where he calls the voice “A white guy doing an impression of a white guy making fun of my father.”

“I was cynical a little bit about whether people would like to hear about it and the Apu stuff in particular just felt so old and discussed to death,” says the comedian, “and Kamau was very clear with me, like, ‘It has not been discussed to death, you and your community have discussed it’…The idea of representation is so second-nature.” After that particular segment went on to be used on classrooms and shared on blogs even after Totally Biased was cancelled, Kondabolu knew there was more there. People wanted to talk about Apu.

He’s had enough. @harikondabolu stars in #TheProblemWithApu, a new documentary premiering Sunday at 10/9c on truTV. pic.twitter.com/VgOK5LGbjS

— truTV (@truTV) November 16, 2017

Told through a cartoonish style with montages and cutouts (budgets didn’t allow for a full cartoon, unfortunately), The Problem With Apu also includes a conversation with Simpsons writer/producer Dana Gould that’s especially telling. Of course, there are countless examples of brownface and Hollywood whitewashing. But are any of these characters as iconic or recognizable as the Kwik-E-Mart manager? “The Simpsons is not just any show, it’s one of the most important shows in American history, it’s still going”, Kondabolu explains, “It’s something that even if you’re not comfortable with discussions of race or representation or interested in that normally—it’s a Simpsons documentary. There’s something right there you’re going to relate to and everyone has seen it in some capacity.”

This popularity is undeniable, and rings especially true when we discover that almost every South Asian actor had heard the Apu voice in some form growing up. Aparna Nancherla, Hasan Minaj, Aziz Ansari, former US Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy, and many of Kondabolu’s interviewees talk about bullying and harassment related to either being called Apu or having that voice used to mock them. “I knew that this was a really great opportunity to open up a bigger discussion about race and representation using the Simpsons as a really great example and the Apu character,” he says. At the same time, Kondabolu emphasizes that while Apu is a relatable example, he’s a small one:

“This isn’t just race. This is gender, this is sexuality, it’s how we represent gender and represent trans folk. This is about the impact of images—how those images are made and when they’re out there, what they can do. All these images—whether it’s preventing people from getting jobs cause people have images of who they are, whether it’s police brutality, whether it’s hate crimes. To be able to dehumanize somebody requires a degree of misinformation and ignorance. The misinformation, you can say, comes from home—but lets be honest here. More than the schools and parents—the media, whether it’s tv shows or the internet, that influence matters much more.

It’s also a conversation that might not have taken place around 1990, as the comedian notes the lack of South Asians in the industry at the time, and the ways that the internet has changed who is heard:

“I think the big thing is, the people whose voices you’re hearing are people who never had their voices heard. We’ve only recently been allowed to talk in the mainstream—and it be our voices and not a white dude literally doing the voice—do you know what I mean?”

He also adds that there are many factors to this shift. “If you have enough people, that’s money. I don’t mean to be so cynical, but a lot of this stuff isn’t about genuine good will or a respect for diversity”, he explains. “It’s ‘If we don’t do this thing we will lose people’s money and there is money to be made and we can’t play those games now.’ I think that’s also part of it. I think the culture has changed and it’s partly driven by that.”

While the comedian is more accustomed to the stand-up format, one where he explains entertainers “have to get to the point faster so you don’t lose people’s attention”, the documentary suits Kondabolu who admits he’s “been accused of being very verbose—just too many words, too many big words.” The 45-minute documentary allows the comedian to approach many more aspects of this conversation—what happens when a South Asian actor takes a stereotypical role themselves? When is an accent ok? What’s the difference between one stereotype on The Simpsons and another? The film goes through several questions with many perspectives, but Kondabolu says, “even then I felt like it wasn’t enough” citing funny moments and ideas that were left on the cutting room floor. “I’m going to be haunted forever,” he half-jokes.

Nearly every South Asian actor in Hollywood is in this documentary and the ones that aren’t, Kondabolu explains, were mostly scheduling conflicts. “It was a nice community moment, that was the core of the film in a lot of ways too, the idea that it’s us talking to each other and other people are going to get the chance to get an honest take.” When I ask how he assembled such a crew, he replies, “I texted most of them. [pause] The community is small!”

.@harikondabolu and @UTKtheINC talk Indian representation in this clip from #TheProblemWithApu, premiering November 19 on truTV. pic.twitter.com/K5pH3wzg9e

— truTV (@truTV) November 8, 2017

He lists them in turn, “Kal said yes instantly which was cool, Aasif [Mandvi] is a friend, Hasan is my comedy younger brother, Aparna is like a sister we’re all close. Ajay [Naidu] is someone I’ve known for years. I had met Vivek a couple times…It’s funny because it’s hard to explain that, but when you’re a small community it becomes a greater thing. We’re all linked in a really unique way. If we don’t know each other, we know of each other or we know somebody who knows somebody else and then vouching is a big deal.” The result is a collective that resists the horrendous tendency within media to force one individual to speak for a group, offering a range of experiences both shared and different.

REMINDER FOR DAY 302 OF TRUMP PRESIDENCY: THIS IS NOT NORMAL (AND NORMAL WASN’T THAT GREAT EITHER)

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) November 17, 2017

Taking a step away from Apu and shifting to the comedy space in general, it’s hard to talk about comedy these days without also talking about the recent revelations that reveal harassment, assault, and sexism behind the scenes. As a fan of Kondabolu’s stand-up and Twitter, I asked him during our interview about a few tweets he had sent about Louis C.K., and how he navigates participating in these conversations.

Multiple people have asked me to comment on Louis CK. However, I don’t think a man’s commentary is what is necessary. We talk enough. We need to finally hear our sisters…and stop being pieces of shit. So I will be Retweeting instead.

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) November 10, 2017

“I feel like there’s something weird about—we’re talking about misogyny and we’re talking about sexual misconduct and the first impulse is ‘What does a random man have to say about it?'” says Kondabolu, “I feel like I understand the idea of male allyship, and I have a bit of a platform and ability to amplify other voices and I know that so many strong and brilliant women who have important takes on it—I’ll just retweet them. At the end of the day, I’m not a primary source in a lot of ways, I don’t have certain experiences.” He later continued this discussion online, tweeting:

Men have forever used privilege & power to elevate themselves at the expense of women. The system is set up for us. To not only allow this, but to then treat women like “the spoils of war” is despicable & all men are implicated. The war is starting to turn. Be on the right side.

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) November 10, 2017

Don’t give me too much credit for being a man who is just saying what we all know. I am also someone who has benefited from patriarchy & who has made mistakes & hurt people. I am doing my best to be the best human I can be & I don’t need a thank you for that.

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) November 10, 2017

Men don’t need a cookie for saying or doing the right thing. We’ve been feasting on privilege for years. WE’RE FULL.

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) November 10, 2017

“It’s bigger than him. It’s much bigger than [Louis C.K.]”, says Kondabolu, “None of it is new or surprising. That’s the weird thing—none of this is new, this is the history of the world. You just hope the people you admire are infallible, but they’re not.”

We’re all implicated in this as men so I’m not taking myself out of it. I’m not holier-than-thou. I’ve certainly benefited from the system and as thoughtful as I try to be, I’ve still benefited because I’m in the position to say the things I’m able to say. And also, I’m sure there were women who could have done what I or other men are doing but they were discouraged from it—discouraged to talk publicly, and I’m not even talking specifically about sexual assault or harassment, I’m talking about in general. Women aren’t encouraged to speak up. They’re not encouraged to share their points of view. They’re not encouraged to perform in this way, in standup, they’re told not to. So, I benefit from that as well. I think it’s bigger than that.

Kondabolu is a perfect guide to this history and examination of The Simpsons’ Apu. The documentary is an accessible, thoughtful, and candid look not only at this character, but a powerful look at what “representation”—a phrase that had become more and more of a buzzword—really means. The Problem With Apu will air nationwide on truTV Sunday, November 19th at 10 ET/PT.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Nov 17, 2017 01:00 pm