BBC Capital has an interesting story about the rise of social media addiction and the cottage industry of therapists, treatment options, detox centers, and—ironically enough—apps that have sprung up to help people get offline. The story has me feeling a lot of different feelings.

Discussing any sort of addiction is a delicate business, and I don’t want to devalue anyone’s experience or desire to get help. But the subject at large—our always-on Internet culture—is an intriguing one, and something that I’ve been thinking about for more than twenty years. I guess that’s why this feels like a personally sensitive topic, but one that I’m keen to dive into and solicit further opinions.

I’ll start this by saying that by most measurable metrics, I’m “addicted” to the Internet. I’ve been online, more or less, since the first AOL floppy disk arrived in the mail. I’ve felt the intense desire to be online since then, and much of my teenage years were spent wheedling and cajoling for more connectivity. Back then, there was a lot of fear and mistrust about the goings-on on the Internet, and it wasn’t considered “normal” for young people to pass the bulk of their time cyberspace.

I spent many, many hours writing fanfiction and playing MUSHes, or “multi-user shared hallucinations,” text-based games dedicated to roleplaying and questing. My mother couldn’t parse my dedication there, and once, despairing, wondered if there wasn’t a way to include the “jobs” I held in online worlds on my college applications. Some friends from the games passed so much time online that they were actually sent to rehabilitation by their panicked parents in the late ’90s.

The irony these days is that those same parents probably now spend a similar amount of time online. With the advent of broadband, wifi and smartphones, many of us are pretty much always connected. The rise of social networks has normalized once-fringe Internet cultures. Grandmothers and your weird uncle spend all day lurking on Facebook. Twitter is essential to politicians, reporters, movie stars and fans alike, and drives cultural commentary. The teens live for Snapchat, Instagram, and cooler apps I probably don’t know about. Internet discourse shaped the course of the American election, for better or worse (for worse). I’m going to hazard a guess that most of us reading this right now are online almost all the time.

So when does the connectivity cross over into a full-blown addiction? The BBC Capital story charts the rise of social media counseling for those who “can’t seem to resist a scroll through your Facebook or Instagram feed during working hours, or … feel anxious when you can’t check your smartphone or have no signal.” That pretty much defines myself and everyone I know in the modern era, but OK. Addiction is a personal thing, and it’s generally up to a person to decide they have a problem and want to tackle it (I think that’s why I still balk at the idea of my online friends who were sent off to Internet rehab against their will).

As our Teresa Jusino pointed out to me, “An addict can become addicted to whatever’s closest.” People can develop addictions to all sorts of things that aren’t dangerous to others, like eating, gambling, shopping. I know that there are those out there who feel as though the Internet has taken over their lives, and their experiences are valid.

If someone is struggling, it’s great that there are a variety of options for treatment. What gets my hackles up about the story is the costs involved: “Hour-long sessions can cost from $150 per hour, with longer detox camping-style retreats costing more than $500 for several days.” Social media addiction is already a privileged problem to have, and apparently, the trendy curative fixes demand even more monetary privilege. And it seems like the industry that’s growing is more about capitalizing on the concern-of-the-moment and “innovating” in that space. For the record, there are free 12-step programs like Internet & Tech Addictions Anonymous if you don’t have that kind of cash lying around.

The addiction is not recognized by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, but therapists specializing in treatment have seen their patient numbers rise. One therapist is quoted as saying, “It’s worse than alcohol or drug abuse because it’s much more engaging and there’s no stigma behind it.”

There’s a lot to unpack in that statement. First off, I have to strongly disagree that social media addiction is “worse” than alcohol or drug abuse, which can ruin lives, relationships, families and flat-out kill their users. While there have certainly been car accidents caused by texting and the occasional story about gamers dying while gaming, let’s not call a reliance on social media worse than the heroin epidemic.

However, the therapist has a point about the lack of stigma around always being online (the fears from my youth have faded). Many of us have sat in a room with family or friends with everyone on their own separate screens and little rules or expectations to govern interactions. I would argue that what’s needed is more etiquette around screen usage, but even that assertion is me coming from a different era than our current young Internet denizens.

The “worse than drugs or alcohol” argument also reminds me of when Dr. Kellogg in the late 1800’s swore that reading was “one of the most pernicious habits to which a young lady can be devoted. When the habit is once thoroughly fixed, it becomes as inveterate as the use of liquor or opium.”

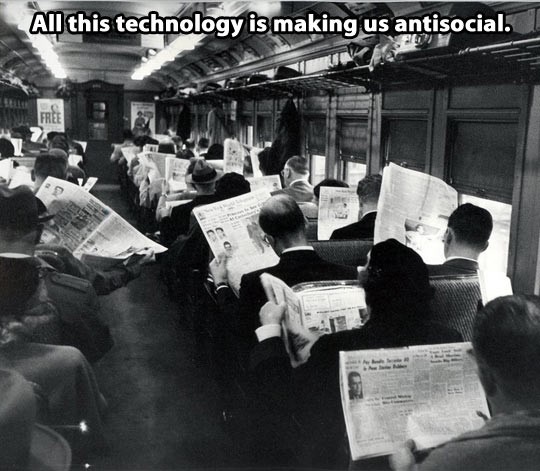

Every advent of new technology has arrived with dire warnings of addiction and disconnect from society. The same alarms were raised about the printing press, telephones, radio, television and the early Internet. (Remember, Victorian doctors like Kellogg thought that reading novels would make women “incurably insane.”) While it might be disconcerting to see a room full of teenagers staring at their phones and not each other, the truth is they’re often interacting in a variety of ways—across apps, networks, messaging and through pictures and video. Who’s to say there’s less value in these interactions? Or that it’s any better or worse than a roomful of folks with their nose in a book or newspaper?

And many people have vastly expanded their social circles through these same networks. Yesterday at a press junket, I joked about meeting a friend from the Internet for the first time a few years ago, and how, because of the moral panics of my youth, I was half-afraid she was going to kill me. The younger reporter I was speaking to deadpanned, “All of my friends are from the Internet.” The number of relationships, romantic and platonic, formed because of our connectivity is uncountable. The value of being able to find like-minded people to share your interests is incalculable.

Several of the start-ups and services around social media addiction rely on being, well, online, which makes me do a double-take. Of the New York-based Talkspace: “The company offers text-message-based therapy starting at $138 per month, with $396 for live-talk therapy. And, while clients use their smartphone to hold therapy sessions, they are being taught how to use the phone in a more mindful way.” However, an important point is also mentioned: “Most people turn to therapy after many failed attempts to control their impulses on their own.” Again, addiction is an incredibly personal and powerful disease and it is not my intention to make light of the problem. When people find themselves unable to control their own impulses in an area, it is hugely important that they can find help when they need it. I’m glad that these services exist.

However, an important point is also mentioned: “Most people turn to therapy after many failed attempts to control their impulses on their own.” Again, addiction is an incredibly personal and powerful disease and it is not my intention to make light of the problem. When people find themselves unable to control their own impulses in an area, it is hugely important that they can find help when they need it. I’m glad that these services exist.

But it is arguable how effective some of the current programs are. “Experts warn of over-relying on mindfulness or digital detox retreats without additional follow-up,” says the BBC story. These might work as quick resets, but do not necessarily address long-term issues. Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center, thinks a lot of our social media fixations stem from there being little by way of training when it comes to connectivity. “We give people driving lessons and swimming lessons, but everyone just gets a smartphone and off they go … There are skills needed to navigate any social space.”

This is the sentiment from the article that I agree with 100%. In my wild west Internet days few parents had any idea what was happening online, but now there’s widespread awareness about cyberbullying, sexting, fake news and other hazards to encounter. I’m no fan of parental controls, but I think talking to your child about social media should be paramount in a world where parents create Facebook profiles for their babies. And I don’t think it would be a terrible idea for adults to have more expectations for each other in place. Just as you wouldn’t pick up the phone at a bar with friends to talk to someone else, maybe try not staring at Twitter or Tumblr the whole time when a friend is sitting across the table from you. I say this both as the person who’s felt ignored and the person doing the ignoring. In this case, I think many of us can afford to be more mindful.

But just as it has with every technological age, the world is changing fast. Soon enough we might have the Internet embedded in our arms and ports in our heads. Maybe the future of interaction is messaging your friend through their smartglasses while you share pints. Maybe we’ll all be hanging out in VR to avoid our hellscape reality. I wish I could tell my worried younger self that the time she spent online learning how to write and obsessing over topics in shared communities would end up being more valuable to her day job than college courses. We don’t know where the future of technology will lead us, but I think by now we should learn to be less afraid of it.

I’m curious to hear what you think, fellow citizens of these here online states. Talk to me in the comments.

(via BBC Capital, image via GaudiLab/Shutterstock. FYI, the image is titled “Confident attractive hipster girl choose real life communication with friends not with technologies prefer spending free time sharing opinions emotion and ideas to posting text in social networks”)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Published: Apr 18, 2017 03:14 pm