Months ago Emily Schorr Lesnick approached us and asked us if we would be interested in running her “localized study of female improvisers” that “looked at how funny women navigate gender on stage.” Naturally, we said “Of course,” “Yes,” and “Yes, please!” Over the summer she adapted her twenty-page senior capstone project to a more blog-friendly format that we’ll be running this week in three parts; one today, Wednesday and Friday.

And so no further introduction from me, here is Part One of Emily’s Funny Women project, an introduction itself.

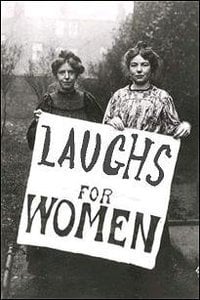

“Women can’t be funny.” This is a mantra repeated both subtly and explicitly in theaters, classrooms, black box spaces, and large performance clubs and venues, a mantra spoken and internalized by men and women alike.

In 2007, Vanity Fair magazine perpetuated this assumption by publishing Christopher Hitchen’s article “Why Women Aren’t Funny.” Someone recently asked Brad Sherwood why women were so bad at improv. This supposed unquestionable assumption that women can’t be funny stereotypes women and their creative capacities and standardizes humor, making men the standard and women substandard.

As a female improviser myself, I was drawn to examine the agenda of this “women can’t be funny” mindset and its impact on female improv performers in the Twin Cities in Minnesota. I began with these research questions:

- How do sexism and misogyny apply to comedy? How do female improvisers navigate sexism and gender roles on stage?“

Awkward.” “Ugly.” “Too Loud.” These are insults used to describe female comedians like Kathy Griffin, Margaret Cho, and even Tina Fey.

Women who demonstrate they can be funny encounter and struggle with sexism in other forms— performing stereotypical roles or roles secondary to men. Since the point of most comedy is to be heard, the historic silencing of women and punishing of “loud” women (labeling women who speak up for women’s rights as “femi-nazis,” for example) negatively affects female comics.

Traditional humor styles often mirror the dominant values of a society, making the public place of the stage a site to act out dominant ideas about gender that devalue women and shore up male power (like throwing words like “pussy” and “bitch” as insults). Consequently, when women do perform comedy, they are not always allowed the opportunity to be funny or witty, and they are set up to be on the sidelines.

I researched the ways sexism and other forms of oppression affect female comics on stage. In this project I explored how women use and manipulate gender and notions of the “comedian” on stage. I considered how the denial of witty women reflects an oppression of intelligent women in public spaces beyond the stage as well.

- When female comics experience sexism on stage, where do they find and exhibit their voice?

I also wrestled with the place of feminism and feminist comedy in these spaces: can comedy be feminism in action? Or are feminists cold and humorless, and therefore do comics need to abandon feminist politics to get laughs?

To answer my questions, I specifically looked at improv comedy, whose unscripted and spontaneous nature allows for “uncensored” release of offensive jokes and oppressive points of view. Also, the live component of improv actively includes the audience in the construction of what is funny. Improvisers adjust their performance based on audience reaction. As one funny woman put it, “It’s equal parts creation and perception” (Anna, improv teacher at HUGE Theater, age 31). Given the mutually constituted production of humor and laughter through live performance, the audience and its gaze are also important dimensions to this performance and its effects. The audiences often reflect the demographics of the improvisers, which are mostly (but not entirely) White, college-educated, able-bodied straight males.

While my research complicates the homogenous image of improvisers, the systemic and systematic privileging of White, straight “maleness” infiltrates improv performance. The specifics of improv’s audiences and performances influence the ways that female improvisers navigate roles dictated by institutions of sexism and potentially sexist audiences. Even so, improv’s unscripted nature can be liberating: by rejecting a written narrative, performers can literally rewrite and tell their own stories.

By combining research and interviews with funny women in Twin Cities, I found that while comedic stages can be oppressive for women and other marginalized people, they can also provide a space for these people to claim agency and respect.

I found that the funny/witty versus pretty division constructed on stage has actually been a part of women’s lives off-stage as well, and the stage is a space for women to wrestle with these roles, to be described in detail in a later installment. My research echoed my interactions with funny women and my own experience: female intelligence is placed in opposition to female beauty, a dynamic that emerges in social scenes and staged performances. So, the stage serves as both a microcosm for social structures, but also a forum for resistance.

Emily Schorr Lesnick is a recent graduate of Macalester College, where she studied identity, comedy, and girl geek culture. Her writing has been featured on FunnyNotSlutty.com and guffawmn.com. You can follow her on Twitter @ESchorrLesnick.