Wonder Woman and the Paternal Narrative: the Rise of Wonder Woman, the Fall of Women

The Arguments from Culture & History

I have read several suggestions for why this change should not be seen as having any significance:

This is just the Amazon’s culture. We can’t blame them for that. You could say the same thing about the Khunds, with their quirky little cultural tendency to conquer inhabited planets and decimate the native populations. Or the followers of Ra’s al Ghul. Or even the Joker, with his little culture of one. There’s a difference between explaining actions and excusing them. In the context of a DC superhero comic book, what the Amazons are doing is murderously evil—the JLA exists to stop people like this and have them locked up for crimes against humanity.

I could buy this argument if we were talking about a race like the Formics (from Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game and its sequels), who were biologically and psychologically totally alien to humans. They were hive minds, and didn’t recognize individual organisms—human beings, or even their own individuals—as anything other than tools of a common mind, so they didn’t recognize killing one as wrong. But the Amazons are human, have sex with human men, and give birth to human babies, male and female. They have no such excuse, only selfishness and violent hatred. I don’t see what makes them different from any other DC villain.

It’s worth noting that, despite this practice being an accepted part of Amazon “culture,” they kept it a secret from Diana (and presumably other new-generation Amazons) even after she became an adult. (She had to find out from Hephaestus.) Somehow they understood that it’s nothing to crow about.

The Greeks portrayed the Amazons this way, so you can’t complain—it’s just history! It’s true that in some (not all) versions of Greek myth, the Amazons are less than kind to their male lovers or male children (although The New 52’s version tends to the extreme even of the Greek versions). But that’s not history; it’s the fictional stories the Greeks told about a group of people they had no contact with. (Most historians believe that the Amazons never existed, and that the stories were inspired by some tribes where both men and women fought in battle, creating a legend of “women warriors.”) And the Greeks were an intensely sexist, patriarchal culture. It is no surprise that they imagined that a group of independent, self-governing women would be strange, dangerous, and a violent threat to men. The problem is, if you unquestioningly incorporate the Greek version into your stories, you risk incorporating their sexist beliefs as well.

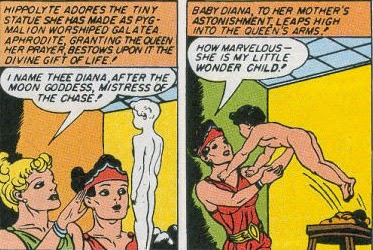

Marston, a well-educated psychologist, would have known all about the original myths. He made a deliberate choice to make his Amazons decent human beings, followers of the goddess of love instead of the god of war, so they could represent a positive view of a woman-centric society—in a genre (and a culture) almost entirely male-centric. His message was that a community of women could be a good, moral, and loving, even without men to guide them. Diana—Wonder Woman—epitomizes them; she takes her values from Hippolyta and he Amazons (and the positive aspects of the goddesses they worship) and brings them out into the larger world.

Azzarello completely reverses this message. His Amazons are not only grotesque, murdering villains, they are villains in exactly the way misogynists claim they would be: man-hating, castrating, androcidal, and—unless stopped by a male god—child-killing. In this version of Wonder Woman, it turns out the sexists were right.

The Amazon & Goddess Influence (or lack thereof)

If Wonder Woman learned her values from these women, it is only because she didn’t understand them. It is stated that Wonder Woman “loves everyone.” She didn’t get that from them—they hate, and they kill the helpless. In addition, young Amazons taunted Diana simply for being different, calling her “clay,” a refrain they return to as adults whenever they are in disagreement with her. Their values are frankly horrible. And Diana’s mother, the queen, does nothing to set them right.

(Both the claim that Wonder Woman loves everyone, and the persistence of the clay origin even as a falsehood, are problematic for reasons that don’t pertain directly to the subject of this essay. I hope to address that in a later piece.)

In any case, Diana doesn’t look to her fellow Amazons for guidance or as role models. Finding an outpost of murdered Amazons (Batwoman #13), Diana says to Batwoman, “I don’t always understand my… sisters. But none deserved to die like this.” I suppose that’s better than “who cares?” but it is not exactly a ringing endorsement of their kinship. She can barely bring herself to call them her sisters.

At this point about the best thing you can say about the Amazons is: well, at least this pit of vipers produced one good female, although it’s a mystery how.

Diana didn’t even really get her fighting skills from the warrior Amazons. Yes, she practiced alongside them. But it turns out that Ares secretly and benevolently trained her. Martial lessons from the (male) god of war trump lessons from the long-lived but essentially human Amazons any day of the week. They don’t really contribute much to her, do they?

The goddesses do not fare much better in this portrayal. In most versions over the decades, Wonder Woman is in conflict with some goddesses (such as Eris), but gets succor and positive guidance from others—they represent something good. In Azzarello’s story, the goddesses of Greek myth are, to a one, petty, shallow, selfish, and deceitful, and Wonder Woman is opposed by every one of them. The sole potential exception is Athena—but she’s offstage for the entire tale. (Ostensibly. The truth is arguably worse.)

Now, it could be said that the goddesses don’t come off any worse than any of the rest of the deities. But this isn’t true—both Ares and Hephaestus seem to be more helpful and selfless than any of the female deities. Hephaestus, in particular, is a model of empathy and care, rescuing the male children that the evil Amazons would have discarded.

Things I’ve Been Told

For Reference’s Sake: Things People Have Told Me About My Opinion On This (with responses)

You just hate change. Not true. There are some changes I quite like. I thought Alan Moore’s change, in Swamp Thing, revealing that the Swamp Thing was not Alec Holland—that Alec Holland was dead and the Swamp Thing was a supernatural creature built on the template of his memories and personality—was brilliant. (Now essentially reversed in The New 52, not a change I like.)

With Wonder Woman, I was ready to be done with the clay origin. It’s charming and has a mythic resonance, but I don’t think it’s essential, and for some people it does make Diana’s origin “confusing.” (Is she human? A golem? Does she have a soul? That kind of thing.) I wouldn’t have been disappointed if they kept it, but this time around I was hoping that Diana’s father would be a human man—decent, kind, but not exceptional—that Hippolyta meets and has a brief affair with during an adventure in Man’s World. (In my imagination, he’s dead by the time Diana becomes Wonder Woman, but she discovers she has human relatives.) I think this would have given her a stronger connection to the world outside Themyscira.

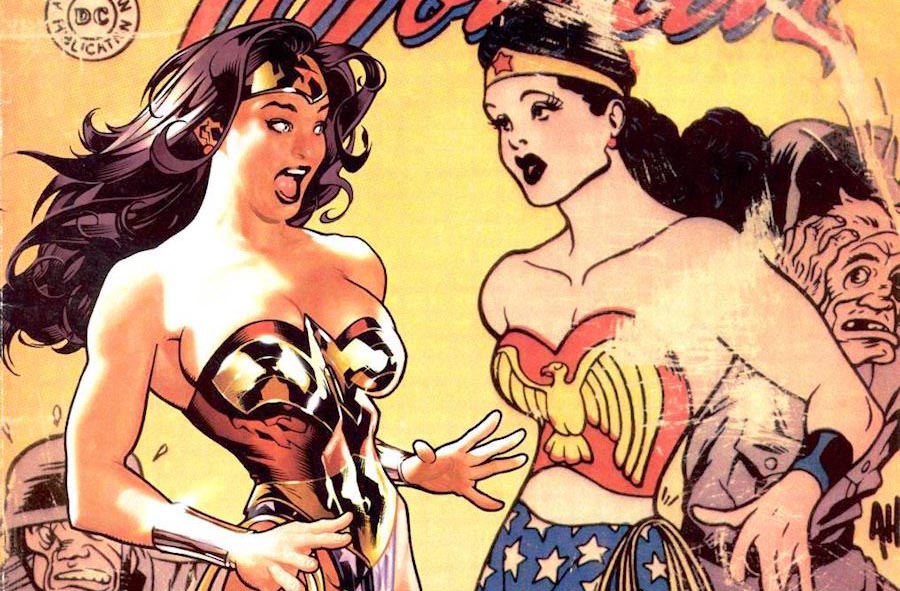

But just because I like some changes doesn’t mean I have to like all changes. I think changing Diana’s tale from a quite rare Maternal Narrative to a highly standard Paternal Narrative, and changing the Amazons from a model of positive possibilities of a community of independent women (not meant to be perfect, but meant to be honorable and worthy) to a picture of the ugliest, most misogynist stereotypes of feminists, completely discards what made Wonder Woman and her supporting cast unique and meaningful, and turns them into the opposite of the pro-women story they were meant to represent. This change I don’t like.

You think fathers shouldn’t be important. No, I just think that making fathers the most important every single time, while mothers take a backseat again and again, sends a sexist message (whether the writer intends it or not). And in this case it is contrary to the original theme of Wonder Woman (which is still an important one), and imposes a unimaginative conformity on her hitherto deliberately non-stereotypical narrative.

The fact that the Amazons are evil and mean-spirited makes Diana even more heroic, because it gives her more to overcome! Do people really think like this? Just as an example, imagine that, in The New 52, Ma and Pa Kent were revealed to have been KKK members who participated in the lynching of several black men. Would readers applaud that revelation, because it would make Superman’s heroism look so much more impressive?

As far as I can tell, nobody—writers, editors, publishers, readers—thought that that change was necessary. The Kents are still wonderful people who instilled their son Clark with strong, positive values, and we still love him as much as ever.

It is quite possible for an author to give Diana challenges to overcome without making the women around her—her family, who once instilled her with strong, positive values—into horrific (and stereotyped) feminazis.

You’re saying Azzarello is a bad writer/a sexist. I’m not. Some of his writing is very good; some of it I have issues with. I’m not the right audience for his grotesque, generically-named gods, but that’s just me. I understand that a lot of people are big fans of his Wonder Woman, and I’m not telling them they shouldn’t be. I’m glad they’re enjoying themselves.

For me it’s not an either/or question. You can be a good writer, and bring something fresh and new to the character, without throwing away the things that made her narrative uniquely female-centric and replacing them with sexist tropes.

As for whether he’s sexist, I doubt it. In any case I’ve never met him; I’m only talking about his work on Wonder Woman. I do wish that he, and everyone involved in the project, had been more interested (than they appear to be, based on the content) in the reasons she was created, and tin the role that she and her supporting cast have played in addressing issues of gender and sexism in the comic-book world. Wonder Woman was never intended to be “just another superhero, only a woman,” any more than Captain America is “just another superhero, only an American.” Changing the nature of the Amazons in Wonder Woman, and the relationship between Diana and her mother and the other Amazons, is not merely cosmetic; it’s thematic. So what new theme is Azzarello communicating with this story?

I understand that some readers consider this unimportant. Amazons killing shipsful of men! Wonder Woman as the girl Hercules! It’s exciting! It’s kewl! That’s all that matters. I’m not one of those readers. I think the stories we tell reflect the society we live in, and influence it. They exist in context, and they’re part of an ongoing discussion that authors and readers have with one another. They communicate messages, sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly. Superhero comics got their start in a very particular era of American history. Because of that, women characters were marginalized, non-white characters rare and highly stereotyped, and gay characters essentially non-existent. And today’s comics trade on nostalgia and familiarity, making powerful—and sometimes quite wonderful—use of what came before. But if we don’t temper that with an awareness of the prejudices that were baked into the old stories, we run the risk of propagating the sexism (and racism, and homophobia) of the past into the present and the future—even without intending to. Just by not paying attention to these issues.

Does that make Azzarello a bad writer? No. In fact, it’s not entirely about Brian Azzarello. The history, the context that makes these issues significant—they’re not his fault. But they are the environment he’s writing in. I simply wish that the creative team responsible for recreating Wonder Woman for The New 52 had been more interested in these concerns. (That may be patronizing on my part. It may be that they have expressed exactly the themes they were going for. That I don’t know.)

You think all female characters must be perfect and saintly. Not at all! Bring on Circe. Bring on the (redundantly-named) Female Furies. I love a good female villain. And I don’t think Hippolyta and the Amazons should be without flaws, either. But you can give them flaws without making them murderously evil, and certainly without making them evil in a way that exemplifies the worst, most misogynistic stereotypes of independent women.

(This is not just a gender dynamics issue. I feel the same way about the Guardians of the Universe. Give them flaws related to their aloofness and hyperrationality? Sure. Make them lying, murderous psychos driven by mad prophecies who—for some reason—never managed to design a working cut-off switch for their inventions? Good way to toss out the whole concept, rather than use it interestingly. I see enough lying, murderous psychos in comics.)

You hate men. My husband will be surprised to hear it. I don’t hate men. And I don’t hate male characters. Certainly I shouldn’t need to explain the difference between that and believing that men don’t need to be a (or, really, the) dominant factor in each and every narrative—especially not Wonder Woman’s.

The End of the Story

As Azzarello’s defining, three-year story approached its end, he did not temper his messages (intended or otherwise) about women independent of men, in the form of the Amazons. If anything, he upped the ante. First, when the Amazons—but not their queen—are restored, and Diana takes on the role as their monarch, she demands that they dedicate themselves to protecting Zeke. “But the child has a….” whines one typically phallus-hating Amazon. Diana—the good Amazon—will have none of it. Also, they must accept their brothers (saved by Hephaestus) onto their island and into their company, to fight alongside them.

Do I think the Amazons should protect an innocent child, regardless of genital status? Of course. The problem I have is that the author has created Amazons who wouldn’t want to—an evil community whose first step towards redemption, dictated by the One Good Woman among them, is to stop being so sexist (!) and help out a male. Somehow the once female-centric Amazon tale has become all about men, and how the Amazons treat them.

The final battle takes place. Diana condemns her eldest brother, the First Born, to another few millennia of soul-destroying solitary confinement, hilariously calling it “tough love!” (If she really loved everybody, including him, she might have done the same—out of necessity—but she would have regretted having to.) And then the story-driving secret is revealed. Zola is not Zola; she is Athena, who, at Zeus’s request (command?) lived a human life as Zola, not even knowing she was actually Athena, and gave birth to Zeus’s child Zeke. And Zeke is not Zeke—he is Zeus! Zeus, king of the gods, the great patriarch, has engineered all the events we’ve seen so that he can experience renewal by being born as (his own) child. Apparently immortality is boring.

Of course, to accomplish his selfish goal, he created a civil war within his immensely powerful family, put the entire race of Amazons at risk of extinction, and occasioned the death of several of his children. He had sex with his own daughter at a time when her ability to meaningfully consent was questionable (as she did not know who she was or who he was), and essentially used her as a living incubator. She seems fine with this. In fact, he has used everybody, with little or no regard for their lives, and could be considered the true villain of the entire piece. But nobody takes him on for that. Diana (who has fought gods right and left) does not rebuke him, much less oppose him. (She saves her one objection for Athena, asking her to allow the Zola persona to continue—for her own sake, yes, but also to take care of the all-important child. The Amazons, it turns out, have pledged to protect, not an innocent child, but the Great Father Zeus himself.) The general attitude seems to be a muted “oh, now I get it.” Because what is more fitting in a Wonder Woman story than acquiescing to the selfish, reprehensible machinations of the greatest patriarch of all?

I doubt that we will ever see, in whatever constitutes the mainstream DC universe in the future, a return to the female-centric Maternal Narrative that, previous to this, has always been an integral and meaningful aspect of Wonder Woman’s story. The Paternal Narrative is too habitual, too customary. It is the zero-energy state of the hero’s journey—once you’re there, it’s hard to tunnel out of. (This is, of course, precisely why it was significant, and interesting, that Wonder Woman bypassed it.) And it’s hard to see how the damage done to the thematic role of the Amazons can be repaired, now that they are murderous, hateful villains, and Diana has mainly defined herself by her distance from the attitudes of her “… sisters.” In order to “fix” the Guardians of the Universe, the writer had to kill them all off and replace them with a different group of Guardians who had been hiding in a pocket dimension for a billion years. It would be hard to implement a similar solution for the Amazons, even if they saw the need.

Of course, anything is possible in comics. But I’m not sure the new creative team, David and Meredith Finch, shares any of my concerns about the representation of female-centric stories, characters, and communities in comic books. One of David Finch’s first comments was “We want her to be a strong — I don’t want to say feminist, but a strong character. Beautiful, but strong.”

Should we be relieved that he’s making sure that Diana, while strong, at least shouldn’t be considered a feminist? And I’ll note that no new creative team on Superman has ever felt the need to say that their character will be “handsome, but strong.” Or even mention handsome at all. I guess it’s assumed.

I don’t want to be unfair. When challenged, David Finch walked back some of these comments. And Meredith Finch’s comments weren’t nearly so tone-deaf. Still, there’s nothing in their new Wonder Woman comics that suggests to me that they are any more interested in Wonder Woman’s Maternal Narrative, and all the themes that went with it, than Azzarello was.

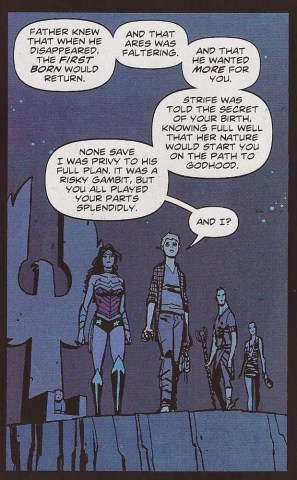

In the end, Athena godsplains Zeus to Diana: “Father… wanted more for you. Strife was told the secret of your birth… [and that started] you on the path to godhood…. You all played your parts splendidly.” In other words, Diana’s father is not only responsible for her powers, and for the relationships and conflicts that have filled her story. He has also planned out her life (without checking with her, of course), and has turned her into the women, goddess, and hero she is today. Diana seems content. This is the Paternal Narrative, supersized.

After all, who would this Diana be, without an all-powerful male figure influencing every aspect of her story? Only: Daughter of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons, granted great powers by the goddesses of Greek myth, who learns the skills and values of her Amazon sisters, and brings them to the larger world as the heroic Wonder Woman.

I don’t think that needed to be cleaned up.

Doctor Bifrost is a software engineer, writer, reader, activist, and big-time nerd. He was brought up on The Lord of the Rings, The Left Hand of Darkness, Greek & Norse mythology, and comic books, which he’s been reading since he was four. He’s still running a D&D game he started in 1982. Doctor Bifrost enjoys well-thought-out world-building and nice merlot. He can be reached at [email protected].

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Pages: 1 2

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]