I’m a huge Universal monsters fan and, for the most part, completely puzzled by the Dark Universe plans that are somehow going to also tie in non-musical Phantom of the Opera and Hunchback of Notre Dame (by the way, isn’t it kind of messed up to call that a monster movie?) adaptations with other films like The Mummy, The Invisible Man, and Bride of Frankenstein.

However, reading Mummy director Alex Kurtzman’s statements on how they’ll bring the 1935 classic Bride of Frankenstein to the present with writer David Koepp and director Bill Condon at the head are making me optimistic about how this particular adaptation may give us a unique and subversive look at the Bride.

“David Koepp wrote a brilliant script. A brilliant script with a very unique structure and a central relationship that I think is gonna be relatable to a lot of people while also being very true to what I believe people love about Bride. Here’s the weird thing about Bride Of Frankenstein,” he says in an interview with Den of Geek, “It is one of the weirdest movies you’ll ever see in your life. It is such a strange film. What amazes me is that the bride doesn’t show up until, what, the last ten minutes of the film? Doesn’t say anything, rejects Frankenstein, he pulls a lever and the building explodes and that’s the end of it. It’s not like she has long monologues, it’s not like you get to know her character, it’s not like she goes out into the world. There’s almost no screen time with her.”

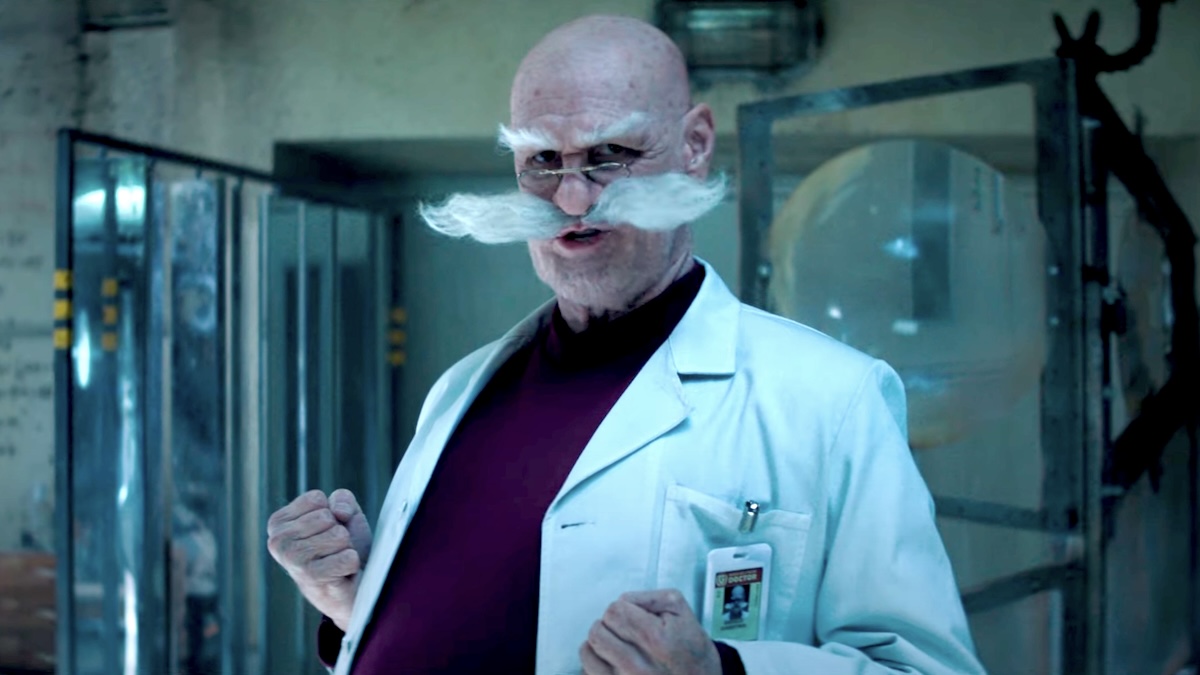

James Whale’s film is, indeed, super freaking weird. Phrases from the first film appear again in different contexts and Ernest Thesiger plays an outrageously camp Doctor Septimus Pretorius who creates homunculi—it’s absolutely enthralling.

There is an interesting duality, where Elsa Lanchester plays both the Bride and Mary Shelley, but with the popularity and iconic image of the Bride, it is somewhat surprising when you first watch the film and realize that she only appears for a small bit. “And yet everybody remembers the iconic look, the hair, who she was,” says Kurtzman, “Articles have been written, there’s Halloween costumes. It’s an enduring character because there’s something mysterious about her and that look, and the idea that she was created to serve another man. Which is gonna be an interesting thing to tackle in this day and age. It might be something we subvert in our film. It will be really interesting to see where we go because I actually think that Bride is maybe a lot more accessible as a character than you may think. Mostly because she’s not really a character yet based on the original Bride Of Frankenstein.”

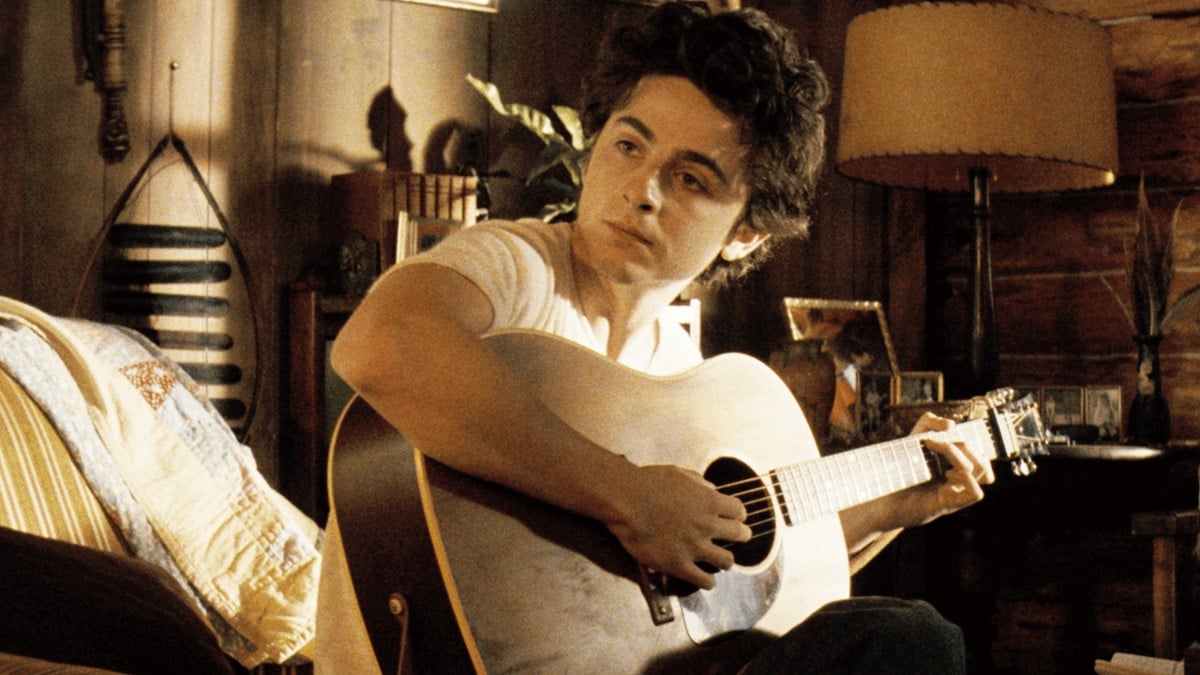

Frankenstein is my favorite book and the Bride has always been a fascinating figure. She never gets a word in Shelley’s book and James Whale only gives her a scream. Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein takes an interesting approach by turning Elizabeth (Frankenstein’s actual bride) into the female monster, yet she also died almost immediately. The focus of this character, for the most part, has been to represent the monster’s desire for companionship and her death then fuels his violent retaliation.

She’s a corpse bride, a trope that we see constantly in horror stories that was immensely popular in Gothic literature. There’s a lot that accompanies this figure—scorn, revenge, tragedy, and melodramatic goodness. Edgar Allan Poe, who loves this figure, once said, “The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” To take this old trope then, and give the corpse bride a voice, to take it beyond poetical musings for a man, would be both relevant and entertaining.

A number of other remakes like The Bride in 1985, or even the 1967 film Frankenstein Created Woman give the bride more attention in interesting ways—I’m curious about what the new Universal take will look like. After all, the power of monsters is that they reflect our societal anxieties and fears. The monster, a figure whose body is assigned danger and violence, is one that has been read in a million different ways: racially, in terms of nation, industrialization, sexually, etc. What kinds of new dangers today would the female monster represent?

Frankenstein readers and viewers have been enthralled with this character forever, trying to interrogate her role in this story that’s full of doubling and concerns itself heavily with how this science of male birth (because that’s what Frankenstein’s creation is) interacts with marriage, gender roles, and the family as a whole.

What do you think about this remake? Does it have potential?

(via /Film, Image: Universal Pictures)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Jun 8, 2017 04:37 pm