Why Deadpool Is A Subversive Character, And How the Movie Could Get Him Right

How did this omnisexual, disabled, "ugly" hero get so popular?

As marketing buzz grows about Ryan Reynolds’ upcoming Deadpool film, I’ve felt a perplexing mixture of excitement and dread. As any long-time fan of the Merc with a Mouth knows, adaptations of this unlikely hero have ranged wildly in quality. I happen to like his 2011 appearance in Marvel vs. Capcom 3, although I have to admit that the game signified a change in Deadpool fandom. As of the late aughts, Wade Wilson had officially gained mainstream attention.

Around that time, Deadpool’s attire would no longer be mistaken for a cheap Spiderman knock-off. The character had somehow turned into a phenomenon, even a meme … but as we all know, memes have a short shelf life. I saw cosplayers donning the red-and-black at almost every con I attended post-2010; they’d scream “Cowabunga,” photo-bomb intricately staged costume shoots, and use Deadpool’s duds as an excuse to be obnoxious. Even my friends who loved the Merc had to admit that he wasn’t “cool” anymore, and a big part of what seemed to be “ruining” Wade’s reputation was his new collection of overzealous fans. It wasn’t just that he was “too popular,” it was that somehow his character had been reinterpreted as “Loud Angry Nerd Guy.” The final nail in the coffin had to be his 2013 videogame — a truly embarrassing misinterpretation of what originally made Deadpool an endearing and enduring character.

Even as the backlash against Deadpool fandom grew, Wade Wilson gained a new and powerful fan in Ryan Reynolds. I’m not sure Reynolds had even heard of the character before playing a version of him in that regrettable Wolverine: Origins film, but that 2009 appearance definitely contributed to Deadpool’s omnipresence in the early 2010s. It also birthed a strange and unexpected determination from Reynolds to get Deadpool a feature film. Bizarrely, this film has come to pass, presumably due to Reynolds’ current A-list status and Deadpool’s own rise in popularity.

If you had told me in 2009 that we’d see a Deadpool feature film starring Reynolds, I’d be overjoyed. But I can’t deny that the past few years have not been kind to Deadpool, and it’s not just because of his crappy videogame … although that’s a symptom of a larger problem. And that problem would be The Flanderization of Deadpool.

(Image via A Critical Hit)

Deadpool began life as a Rob Liefeld sketch that bore striking similarity to Teen Titans‘ Deathstroke. Writer Fabian Nicieza decided to lean into the joke by rhyming Deadpool’s mild-mannered persona with “Slade Wilson,” Deathstroke’s name. It didn’t take too long for Deadpool’s fourth wall winking and lampshade-hanging to begin in earnest. Once the character had been embraced as a parody of “grim-dark” villain tropes, I would guess it seemed only natural for his writers to use him as a mouthpiece. Joe Kelly’s Deadpool books from the late ’90s often get cited as the origination of the character’s dark humor stylings; those volumes gained a small but steady cult following at the time.

Deadpool’s greatest superpower is his self-awareness (well, that and the healing factor). He refers to his own canon, talks to other characters about their story-lines by referring to literal issue numbers, and acknowledges his own over-the-top persona. Unfortunately, this self-awareness gets painted in-universe as “crazy.” Deadpool knows himself to be a comic book character in a world of other comic book characters, but since he’s the only one who knows this, he’s seen as delusional.

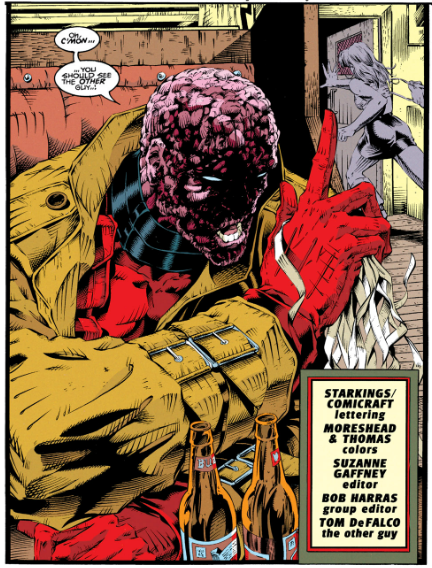

The portrayal of Deadpool’s mental illness has some subversive qualities, although it’s not without its share of ableist implications. Deadpool’s ability to “see” his own fictional circumstances is explained away as a side effect of his deteriorating physical form. Deadpool’s healing factor has some unusual effects on his body, specifically his brain; plus, Deadpool has cancer, and although his powers allow him to continually heal from the disease’s effects, he’s not exactly pain-free. (As Hollywood’s Wolverine might say, it hurts every time.) Because this is a “magical” twist on chronic pain, though, the writers can get away with justifying a lot of weird stuff. Such as the fact that Deadpool knows he’s in a comic book.

Still, I like that Deadpool has been consistently portrayed as a character with a sense of humor about his circumstances, rather than as a tragic figure. After all, he’s meant to be a parody of over-dramatic comic book characters, especially “crazy” villains. Unlike the ableist stereotypes of DC’s Arkham Asylum inmates, Deadpool’s happy-go-lucky attitude has always struck me as a subversive commentary on how “sick” characters are supposed to behave.

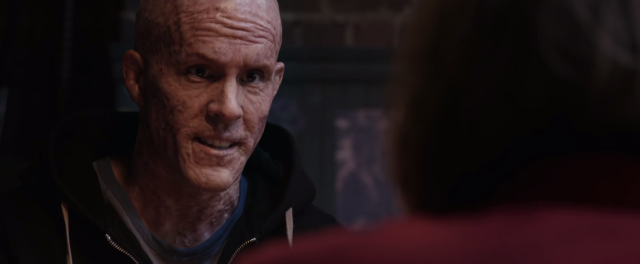

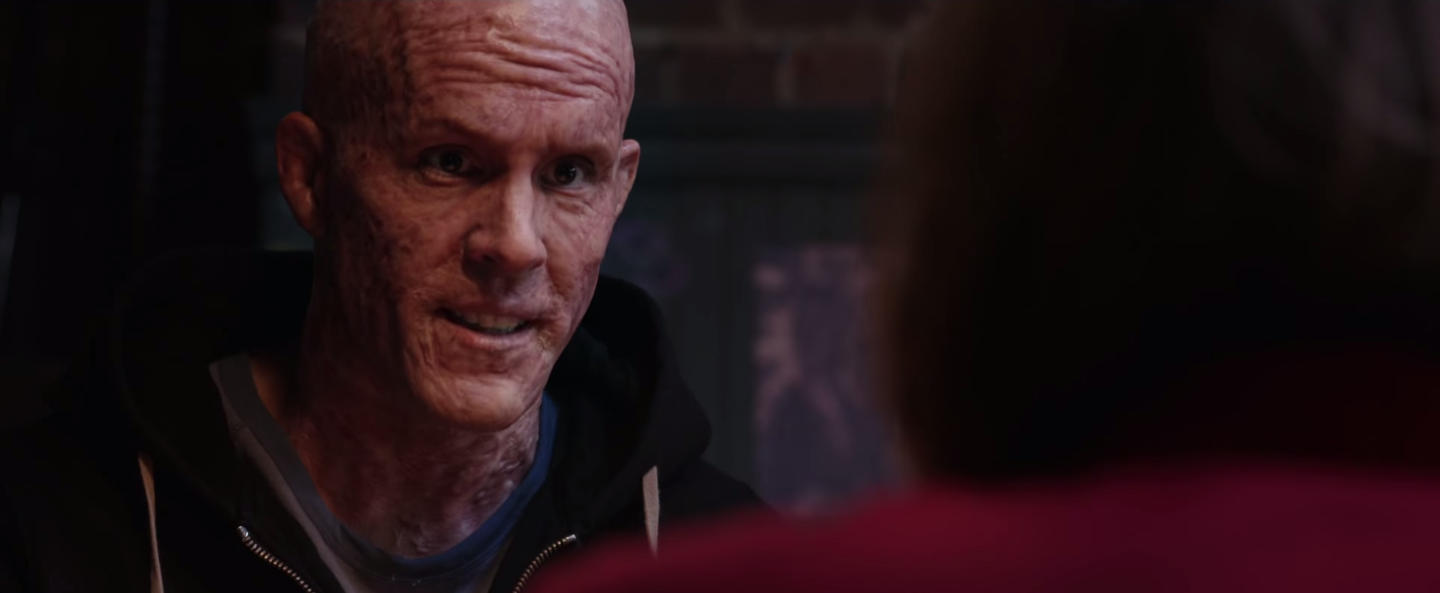

Ryan Reynolds’ film looks like it will play with this concept as well. Wade Wilson still has his zany personality in the trailer even before he undergoes superhero surgery, and although the implication seems to be that his new powers will “make” him even wackier, I do like that he’s got a sense of humor at the outset. I don’t know where the film is going to go when it comes to the “crazy” angle. Still, though, I felt relieved to see that Ryan Reynolds’ interpretation will still feature the physical disfigurations by which Deadpool is known, and that Reynolds’ Deadpool will have a sense of humor about it, too. (“Like a testicle with teeth.”) I did worry that Reynolds’ pretty-boy face would not do unmasked Deadpool justice.

Unfortunately, though, I doubt that this film will make any reference to Deadpool’s omnisexuality (which is canon). I don’t even know whether to hope for any subversion at all, even though I maintain that Deadpool as a character has the potential to offer some pretty interesting takes on our country’s current health care troubles. In his youth, Wade Wilson was a teenage delinquent with a dead mother and an abusive father; he ended up serving in the military, then turned to a career in mercenary work, due to having been forgotten by an uncaring system.

I’ve heard theories that early Deadpool could even be interpreted as a commentary on the after-effects of the Vietnam War, as well as how often military veterans get forgotten once they return from service. All of this social commentary gets served up alongside a hot plate of chimichangas, of course, so it’s no surprise that Deadpool’s story hasn’t been taken seriously by many. Deadpool doesn’t take his own story seriously, either … which is subversive in and of itself, especially in a media landscape packed with mopey Batmen and greatly-responsible Spider-Men.

I understand why people feel sick of Deadpool. It’s because the subversive elements of his story are too often undercut with crappy jokes, lazy interpretations, and – yes – overzealous bandwagon fans who somehow see him as “cool” as opposed to, y’know, parody. I don’t mind at all that most fans of Deadpool didn’t start reading him until after the Wolverine movie came out, but I do mind when I see his character get oversimplified; his 2013 videogame portrays him as an oily, unfunny, misogynistic reference machine. Deadpool’s sense of humor varies according to who’s writing him, but personally, I think he works best when he’s calling out other characters on their clichés – and even calling out himself for his own mistakes.

In other words, the main reason why Deadpool seems groan-worthy these days is because nerd culture has become awash with nostalgic cash-ins and self-referential tripe. Simply making a reference to another piece of media does not constitute a joke. It never really did – but it’s a trick that used to work on us. Everything from Family Guy to Ernest Kline’s Ready Player One capitalized on that reference-happy spirit in the late aughts and early 2010s; obviously Ernest Kline has continued to try to cash in on that nostalgia, but I doubt I’m the only one who feels a bit soured by it all. I think many people associate Deadpool with that and other similar “nerd-gasm” reference points, for better or for worse, since Deadpool did rise in popularity during the same time period.

That said, I don’t think it’s entirely fair to write Deadpool off. Sure, some interpretations of him make him seem like a collection of “nerd culture” hogwash. But couldn’t one argue that his characterization is also meant to call out the worst habits of comics, and to subvert any attempt to box in the Merc himself? Isn’t Deadpool exactly the type of character who one might call upon to make a commentary about the very idea of nostalgic cash-ins? Is Deadpool himself a nostalgic cash-in??? And even if he is … he could still comment on it.

What’s more, I believe that Deadpool’s fandom is a lot more diverse than the obnoxious bros who take up his mantle at conventions and believe him to be a reflection of “their” values. I’m sick of those guys, and I’m sick of their interpretation of the character. But I’m not sick of Deadpool. And I have hope that he will someday be celebrated for something other than his meta-references, and instead, revered for his incisive, biting self-awareness. Ideally, too, that self-awareness would be the trait that his fans would most want to imitate.

(images via A Critical Hit and Tumblr)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]